The governor wasn't ready for last call.

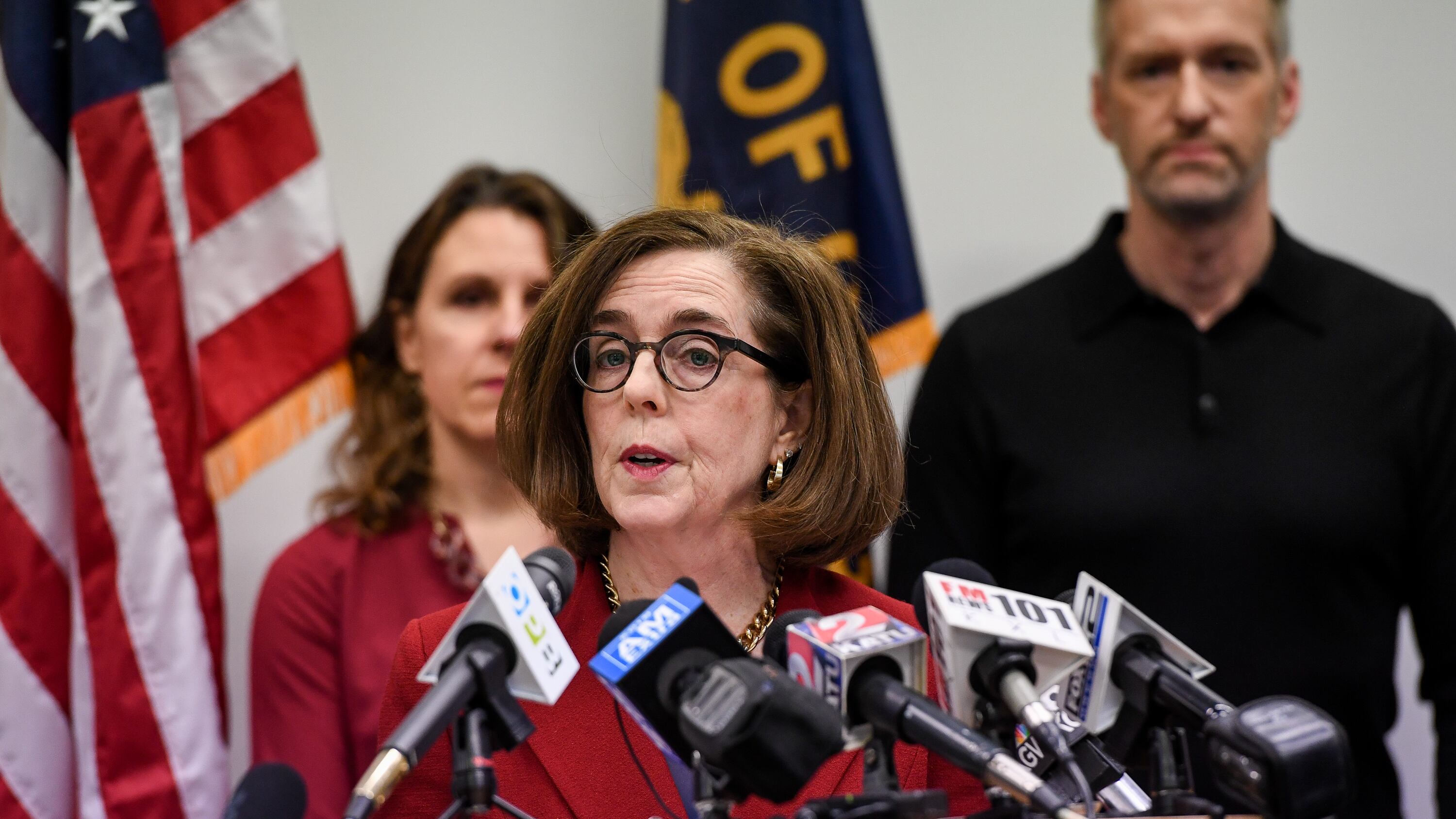

On the evening of March 15, a day after the first Oregon death from the COVID-19, Gov. Kate Brown told the media that she was weighing whether to shut down of all restaurants and bars in the state. The speed of the virus' transmission was outstripping hospitals' forecasted ability to treat patients, and one way to slow the spread was to force people to stop gathering for food and beers.

A few days earlier, the governor had banned crowds larger than 250 people—effectively cancelling all concerts and sporting events—and shut down public schools for two weeks. But Brown knew that taking the next step, closing restaurants and bars, would put thousands of people out of work, and send small-business owners into a limbo from which they might not return.

"We're looking for an Oregon solution," Brown said.

The governors of Ohio, Maryland and Massachusetts had already issued similar edicts. Minutes later, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee joined them.

By the next morning, March 16, Brown still wasn't ready to make the hard decision. She explained that elected officials in rural Oregon towns had warned her that senior citizens depended on local diners for daily meals. She told the press she wasn't ready to act.

Four hours later, she did—shutting bars and dine-in restaurants for four weeks, with only takeout and delivery service allowed.

During those four hours, WW has learned, Brown was pressured into action by several Portland officials, including Mayor Ted Wheeler, who was preparing to possibly close Portland restaurants if she didn't.

That's been a pattern over a frantic week. In the face of COVID-19, Oregon has issued some of the nation's most restrictive social-distancing policies. Yet the governor has been repeatedly compelled to act by others, including Wheeler, Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury and the heads of major hospital groups.

Some officials question whether Brown understands the urgency.

"I'm happy that we have finally moved toward mandating closures," says Portland School Board member Rita Moore. "I'm worried that we don't know if we have moved fast enough."

To be fair, the situation facing Brown has been unprecedented. And what she has mandated is a civic shutdown on an enormous scale. But residents have felt whiplash from the governor's contradictory announcements mere hours apart.

The mixed messages can be explained in part by the backdoor negotiations—and sometimes public pressure—from others ready to take action if Brown would not.

Brown's spokesman Charles Boyle says any criticism of the governor is misplaced. "Gov. Brown's priority is protecting the health and safety of Oregonians," Boyle says. "This is a rapidly-evolving global pandemic, and the timing of local needs changes rapidly as well. Her focus will remain on protecting the public health."

The criticism of Governor Brown's response extends to March 3, when, in a letter to Vice President Mike Pence, the Trump Administration's point man on COVID-19, Brown wrote that Oregon had ample testing kits.

"We are not requesting additional kits from the [CDC] at this time," she wrote.

That position almost immediately changed. Since then, Brown has requested many more lab kits and has complained that the state has only received some of the equipment Pence promised her. The governor has repeatedly sounded that note in her almost daily press briefings—that the feds are failing Oregonians.

The federal failure is undeniable—but observers say there are plenty of aspects of Oregon's response to COVID-19 that Oregon can control and that Brown has been tentative and indecisive in her actions.

Professor Chunhuei Chi, the director of Global Health at Oregon State University, has studied the way countries around the world have fought COVID-19. Chi says

Brown's response to the global health threat "was a little bit slow."

Brown's lack of urgency around getting test kits from the feds became, in the eyes of some observers, a pattern. "There are governors, including Inslee right across the river, who are taking a much bolder stance," Moore says. "I would encourage Oregon state leadership to follow suit."

Curiously, the first organization in Oregon to take aggressive action of any sort in Oregon is a state agency that is a perennial punching bag. On March 3, the Oregon Department of Human Services implemented influenza protocols at nursing homes and senior living facilities around the state.

"I don't know if we were the first but were amongst the first states to do that," says Jim Carlson, the president and CEO of the Oregon Health Care Association, which represents nursing homes, assisted living and home health providers across the state. "By taking aggressive action early, I think we have slowed the number of cases and that's attributable to flipping the switch [two weeks] ago."

In contrast to the speed of that decision, Brown waffled on how to handle public schools and other places people gather, such as bars and restaurants.

On March 11, after a call with superintendents, she said school closure was unlikely. But the next day, two metro area school districts, Tigard-Tualatin and Lake Oswego, took the decision out of Brown's hands. Both districts voted late Thursday afternoon to close and late that evening, Brown hurriedly extended closure to the whole state.

She attributed her abrupt shift to school districts discovering they faced major staffing shortages and an unreliable pool of substitutes. "I considered the superintendents my experts," she told media.

Multnomah County Chair Kafoury publicly called for school closures in the Portland Tribune, several hours before Brown announced a decision. (Kafoury had also proposed limiting gatherings to 100 people before Brown announced a limit of 250.) Then Kafoury closed all Multnomah County Library branches on March 13—a clear signal of urgency to Brown going into the weekend.

Kafoury has an unusual level of closeness to the governor: Kafoury's husband, Nik Blosser, is Brown's chief of staff. So for Kafoury to act unilaterally seemed to several political insiders like a way to press Brown forward to use her far greater powers to shut down bars and restaurants.

Others just demanded it aloud.

Kurt Huffman, whose company ChefStable provides back office and staffing support for 20 of the city's leading eateries, agreed with his partners to voluntarily shut them all down for at least four weeks starting March 15, the Oregonian first reported.

When Brown still hadn't acted on Monday morning, one of the many public officials who'd been quietly pushing for closure broke her silence.

"I believe it is our obligation to be closing bars and restaurants across the state," Multnomah County Commissioner Sharon Meieran, an emergency room physician, told WW after no announcement was forthcoming Monday morning.

"It seems not doing this is putting politics above public health, and even the CDC—they have not been known for their proactivity—is going above what we are doing in Oregon."

That was enough. Brown issued the order two hours later.

On March 17, Kafoury and Wheeler jointly announced they would suspend evictions within Multnomah County, a step Brown told reporters she wasn't ready to make statewide.

The pandemic is far from over and there will be plenty more decisions for Brown to make. The stakes will be high.

"We need to treat this like World War III," says Chi, the OSU professor. "It's a matter of our survival, both of human life and of our economy. If this becomes a prolonged war, it will become something like the Great Depression."