It's easy to laugh off the beliefs of QAnon supporters like Jo Rae Perkins as ridiculous. But for a growing number of Oregonians, the traumatic trifecta of 2020—virus, protests and wildfires—confirms their long-held belief that Democrats are engaged in a sinister plot.

"That psychological appeal of conspiracy theories is very powerful for people who are economically dislocated and socially dislocated," says Randy Blazak, a professor at Portland State University and an expert on extremism. "The added problem with COVID is now people have way too much time on their hands."

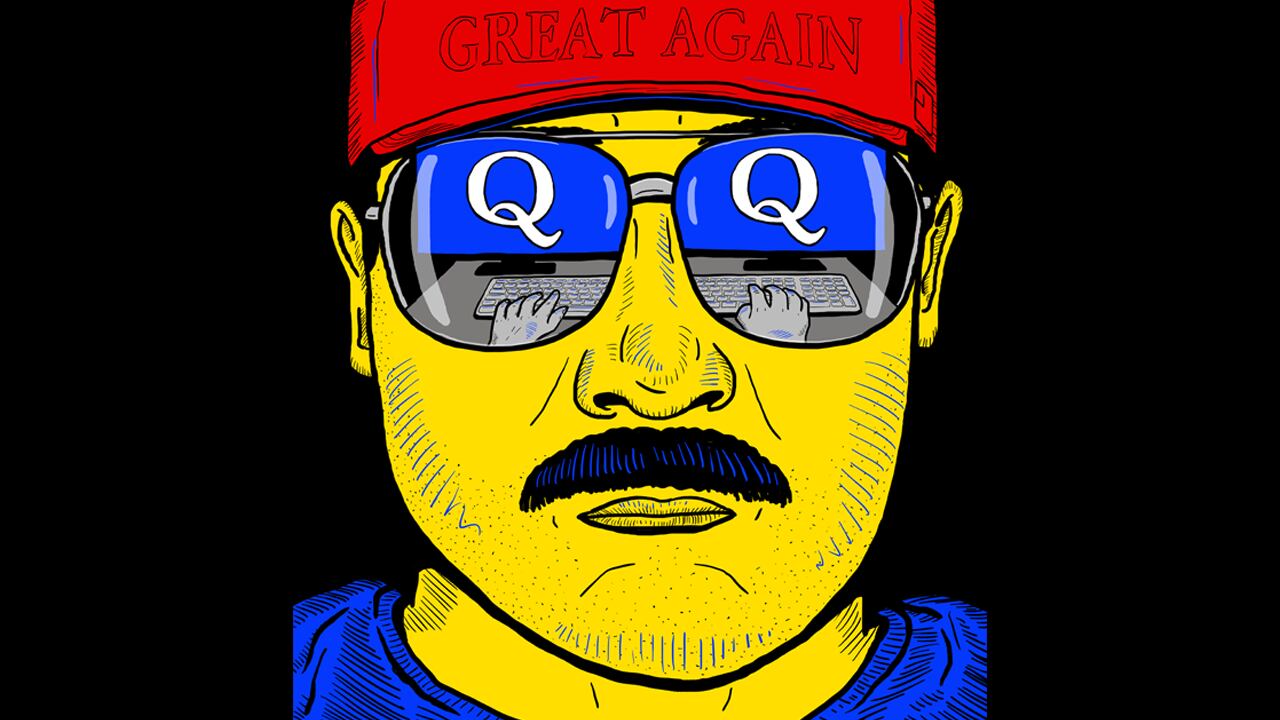

The belief system known as QAnon first began in October 2017 when an anonymous user now known as "Q" posted on 4chan predicting the imminent arrest of Hillary Clinton.

Clinton was, of course, never arrested. But many who follow Q, known as "anons," believe she was. And after that initial posting, Q continued with more "Q drops," including the theory that Democrats were running a child sex-trafficking ring in the basement of a Washington, D.C., pizza parlor, the theory known as "Pizzagate."

Its followers believe Q is one or a few military insiders who have proof that corrupt leaders worldwide are part of a treasonous cabal. The eventual destruction of that cabal is imminent, thanks to President Trump. But it also requires the support of dedicated patriots who can follow Q's clues—Trump can't do it without their help.

"People will call it the echo chamber, but echoes fade. This is just getting magnified and going louder and louder," Blazak says. "Ticking time bombs are a recurring theme in these groups, that you have to act and you have to act now."

QAnon doesn't have a political platform—its adherents don't all ascribe to the same views on, say, tax policy or same-sex marriage. Instead, Q followers believe in something completely off the grid of traditional politics: Almost everyone in power—particularly, but not exclusively, Democrats—are involved in a cover-up of sex trafficking and corruption. That rot infects the highest levels of government and the richest people in the world, like George Soros and Jeffrey Epstein. In fact, to many Q supporters, Epstein wasn't an outlier—he was one of hundreds of similar abusers of power worldwide.

Such a belief may sound like a bizarre new phenomenon, but it's already seeped into the 2020 election cycle. Media Matters reports that at least 75 Republican congressional candidates expressed support for QAnon, 22 of whom made it onto the November ballot.

"QAnon's reach has broadened significantly in 2020," says Lindsay Schubiner, a program director at Western States Center, which tracks right-wing extremism. "There's a lot of overlap between QAnon and other far-right and alt-right movements, but it certainly has uniquely identifiable origins and slogans and other signifiers."

Blazak says similar paranoia about federal bureaucracy has roots dating back to the John Birch Society in the 1960s. But the election of President Barack Obama—the nation's first Black president—fueled rapid growth among far-right conspiracy theorists.

Blazak describes conspiracy theories as a "funnel" that gets darker and more radical as you delve deeper. "It becomes really soaked in conspiracy theories about shadow governments. The granddaddy of all is the anti-Semitic theory of a Jewish cabal. If you follow those folks down the rabbit hole, it gets really dark."

And at rock bottom? Blazak says, "You get to violent revolution."

For people like Beverly Jenkins, though, any attempt to discredit Q only intensifies her belief that it's real. The derision she receives? That's part of the cover-up.

"They like to say it's a cult. It's not a cult," says Jenkins, a LaGrande, Ore. resident who brought a homemade letter Q to a May rally in Hermiston. "They have tried to debunk it but they can't. It's a worldwide event—this whole plan to take down these corrupt people who've been running this world."

Read the cover story: A candidate for Congress is bringing the Qanon conspiracy theory to a baseball stadium near you.