When Oregon lawmakers met to redraw the state’s legislative districts last month, many incumbents got to keep their seats.

One didn’t fare so well: a Democrat who had questioned the integrity of the redistricting process central to the leadership of House Speaker Tina Kotek (D-Portland).

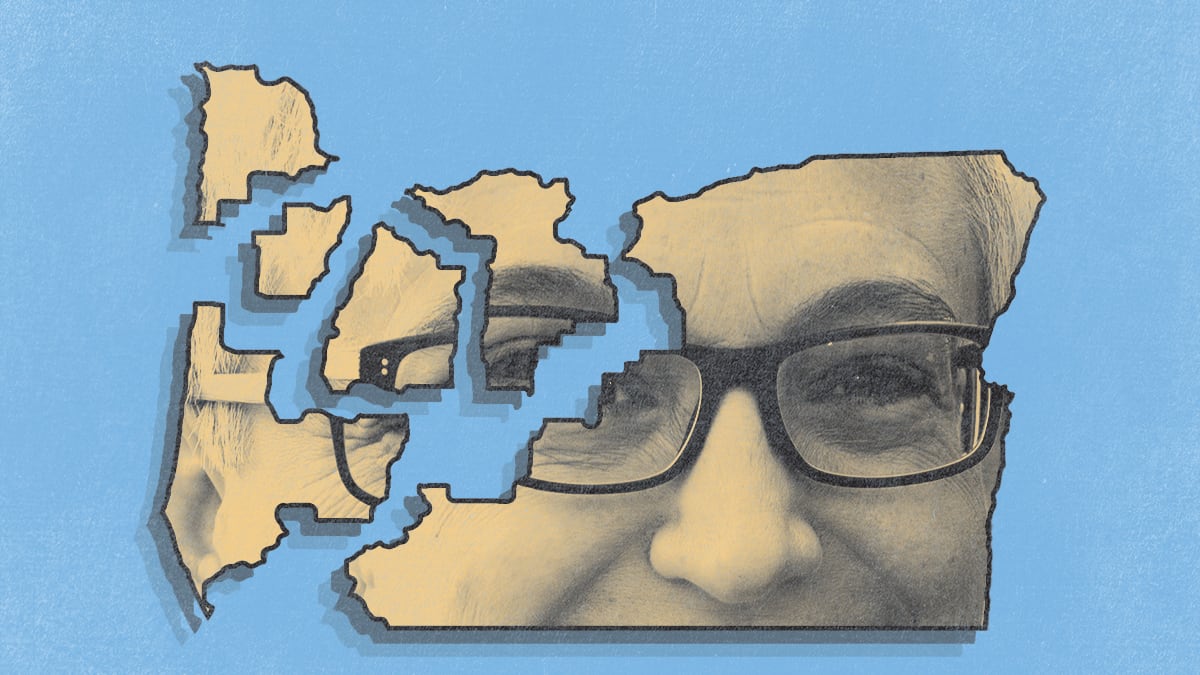

Fellow Democrats who controlled the process redrew Rep. Marty Wilde (D-Eugene), one of their own, out of a Democratic majority district representing Eugene and into one where he’ll likely lose if he runs again. In his new district, Republicans outnumber Democrats by 5 percentage points.

Wilde couldn’t attend the special session where he was voted out of a Democratic district and into a Republican one. He had been called up for National Guard duty to support Oregon’s hospitals as the surge of COVID-19 cases continued to overwhelm some parts of the state.

Wilde isn’t talking, owing to military rules about politicking while on duty. He is on National Guard assignment through the end of October.

Others say he got a raw deal.

“It was intentional, and it raises questions,” says Rep. Brad Witt (D-Columbia County) of how Wilde and he were treated. Witt is the other Democratic lawmaker redistricted into a Republican majority district last month.

Wilde is in just his second term as a legislator.

According to multiple sources familiar with Wilde’s plight, Wilde had violated the protocols of Kotek’s chamber by attempting and failing at an aggressive maneuver to bring a bill he sponsored to the floor on the final day of the legislative session. (It would have banned boats over a certain size from pulling anyone riding waves behind them.) He had also openly challenged Kotek’s handling of the redistricting process, saying his fellow Democrats had twisted the boundaries of his district to achieve electoral success.

A spokesman for Kotek says it wasn’t personal, just business. “The committee’s work to develop new district boundaries was not personal in any way, and to suggest otherwise is just completely false,” says spokesman Danny Moran.

In an email several days before he went silent, Wilde blamed the Senate Democrats for his fate.

“I have it directly from both you and the Senate Ds that this was insisted on by the Senate, even after Tina advocated for me after I pointed out that swapping rural parts of HD 8 for the only urban precinct in HD 12 would actually accomplish the goals of both parties,” Wilde wrote to House colleagues on Sept. 21. “I had the temerity to speak up, and I was punished for it.”

House Majority Leader Barbara Smith Warner (D-Portland) disputed the critiques.

“It’s ironic that legislative Democrats have been accused of being too partisan, and now apparently not partisan enough,” she says. “This is a good indication that the maps were drawn appropriately and legally. Redistricting shouldn’t be about making politicians or pundits happy; it’s about serving the needs of the people of Oregon, and that’s how the committees operated. The maps reflect the voices and needs of communities across Oregon, even if it makes a few politicians unhappy.”

Democrats say they were responding to the need for communities in the Eugene area to be better represented in Salem and that the rural areas of Columbia County represented by Witt have become more Republican.

“Two major considerations that we are not allowed to consider in drawing maps are partisanship and where incumbents live,” says Rep. Andrea Salinas (D-Lake Oswego), who led the redistricting effort. “That means that inevitably—if this process is undertaken appropriately and legally—there will be sitting legislators who end up in the same district with each other, and some legislators who don’t like the composition of their new districts. Legislative seats don’t belong to legislators but to their constituents.”

Perhaps so. But just a handful of sitting lawmakers—Democrats and Republicans—found themselves in unwelcome territory after the process was finished.

Kotek faced a daunting task in the special session: Her party needed to draw new maps to reflect Oregon’s population gains after the 2020 census—and the state’s expanded Democratic majority—without alienating Republicans so completely that they refused to participate.

Some advocates say Kotek found a clever incentive to offer Republicans in exchange for sticking around: Most maps preserve incumbents’ seats and, in some cases, make previously competitive districts less so.

“An incumbent protection gerrymander” is what Sal Peralta of the Independent Party of Oregon calls it.

That may be a clue to one of the mysteries of the redistricting session:

House Republicans did not walk out over their objections to the maps. They didn’t get maps they considered fair, but they preserved their chances for reelection.

The maps passed by the Legislature largely preserve incumbents, with exceptions that sometimes prove the rule by sacrificing legislators who planned to leave anyway. On the Democratic side, Sens. Lew Frederick (D-Portland) and Michael Dembrow (D-Portland) were put in the same district, but Dembrow has said he will not run again. Sens. Lee Beyer (D-Springfield) and Floyd Prozanski (D-Lane County) are now in the same district, but Beyer has said he’s retiring. On the Republican side: The district of Rep. Bill Post (R-Keizer) now has a Democratic advantage, but he announced his resignation, effective Nov. 30.

Four Republicans face tough races after their districts were redrawn:

Rep. Daniel Bonham (R-The Dalles) faces a reelection fight against Rep. Anna Williams in a Hood River district that is more Democratic. Rep. Raquel Moore-Green (R-Salem) is now in a more Democratic than Republican district, though the incumbent, Rep. Brian Clem (D-Salem), has said he won’t run again. Sen. Kim Thatcher (R-Keizer) faces a difficult reelection bid should she choose to run again. Sen. Bill Kennemer (R-Canby) now has a Democrat-heavy district; he says he’ll run again despite the odds.

One pair of Democrats in downtown Portland, Reps. Maxine Dexter and Lisa Reynolds, were drawn into the same district, though Sen. Ginny Burdick (D-Portland) has said she will not run for reelection, leaving an open Senate seat in the area.

That so few Republicans were harmed in the making of the maps makes Wilde’s fate all the more notable. That’s especially true because he challenged the integrity of the process before being called up by the Guard.

Wilde’s Aug. 16 newsletter warned of problems with the existing map for his district. The University of Oregon, among other institutions, was split into different districts, what’s called “cracking” in the informal terminology of gerrymandering—splitting Democratic voters among districts.

“The problem is that communities of shared interests are split among different districts, which limits their ability to represent their interests effectively as a group,” Wilde wrote. “I hope that the new district boundaries will address that issue.”

Wilde succeeded. The university won’t be split.

But one precinct in Eugene got singled out for inclusion with the rest of Lane County: Wilde’s.

“It defies logic,” says Shaun Jillions, a corporate lobbyist with the advocacy group Fair Maps Oregon, which opposes gerrymandering. “Look at the map.”

Wilde hasn’t said what he’ll do next. After all, he can’t discuss politics until next month.

“He’s such a good guy,” says the Independent Party’s Peralta. “He’s been so fair minded. He was acting like a brake and conscience on some of what the Democrats were doing.”

This story has been updated since publication to reflect that Wilde blamed Senate Democrats for the redistricting that cost him a sure reelection.