Gov. Kate Brown’s best day in office might have come a little over two years ago.

It was Aug. 28, 2019. Brown, in a blue blazer and pearls, traveled to Portland’s Jefferson High School to sign the Student Success Act, a tax on corporations that would kick a billion dollars a year of new money into K-12 schools.

“We know the future of Oregon depends on you—and you are worth every penny,” Brown told the students.

In many ways, that bill marked the pinnacle of Brown’s tenure as governor.

The bad days were more numerous. A mass shooting that left 10 dead (nine plus the shooter) at Umpqua Community College (2015). A 41-day siege at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge (2016). Historic wildfires (2017, 2018, 2020). And of, course, the COVID-19 pandemic (still going).

It is an unenviable list of crises—and one that has contributed to Oregonians not only losing faith in the governor they twice elected by healthy margins, but sending her popularity through the basement floor.

On Nov. 18, Morning Consult, a national polling firm, reported that Brown’s approval ratings were the lowest of any governor in the nation: 50th out of 50.

Portland pollster John Horvick of DHM Research says Morning Consult’s findings are consistent with his firm’s numbers: Brown’s standing with Oregonians is on a par with former President Donald Trump’s marks during his administration.

Brown’s lousy poll numbers could influence next year’s governor’s race—and threaten Democrats’ possession of an office they’ve held since 1987.

Even her allies appear wary of getting her public support.

“If she’s interested in making an endorsement, I would certainly talk to her about it,” House Speaker Tina Kotek (D-Portland), who’s running for governor next year, told WW diplomatically.

Brown’s unpopularity puzzles supporters because, in addition to the Student Success Act, she can point to an impressive list of progressive policy wins.

Brown signed the biggest transportation funding bill in state history in 2017. She presided over a rise in the state’s high school graduation rate from 69% when she took office to 83% last year.

In the past five years, she signed new laws providing health insurance to all children and nearly all adults, secured some of the nation’s most aggressive minimum wage increases, and cemented the nation’s broadest access to abortion. Other victories included family medical leave, rent control, an end to single-family zoning; the effective demise of the death penalty, a half-billion dollars for new affordable housing, and the closure of Oregon’s last coal-fired electrical plant.

Brown also dramatically reshaped Oregon’s courts, naming record numbers of women, people of color and LGBTQ+ lawyers to the bench.

“Democrats have accomplished much of what she set out to do,” Senate Minority Leader Tim Knopp (R-Bend) acknowledges. Republicans had so little influence they stopped showing up for work—the only way they could block Democratic bills from passing.

Brown didn’t get much credit for the legislative accomplishments, and that’s unusual for a governor or a president, who usually get the credit for lawmakers’ work. “This has been something we’ve been seeing almost through her entire time in office,” says Pacific University’s Jim Moore, who is writing a biography of Oregon’s last Republican governor, Vic Atiyeh. “When Democrats get their agenda through, she might show up to sign the bill or say, ‘We did it,’ but people still focus on Tina Kotek or [Senate President] Peter Courtney.”

As it has been for much of Brown’s tenure, the economy is stronger in Oregon than in most states. The state’s per capita income recently rose above the national average for the first time in 50 years, and the poverty rate is the lowest since the 1970s.

Some Salem insiders, such as Jim Carlson, the recently retired CEO of the Oregon Health Care Association, salute her.

“Every governor back to Tom McCall (1967-1975) sought to diversify and stabilize the tax base,” Carlson says. “She’s the one who got it done. It was a major accomplishment that eluded every one of her predecessors.”

In recent months, Brown has also inserted herself in high-profile conflicts, brokering compromises between environmentalists and the timber industry on forest practices and among warring factions on the billion-dollar widening of Interstate 5 through the Rose Quarter.

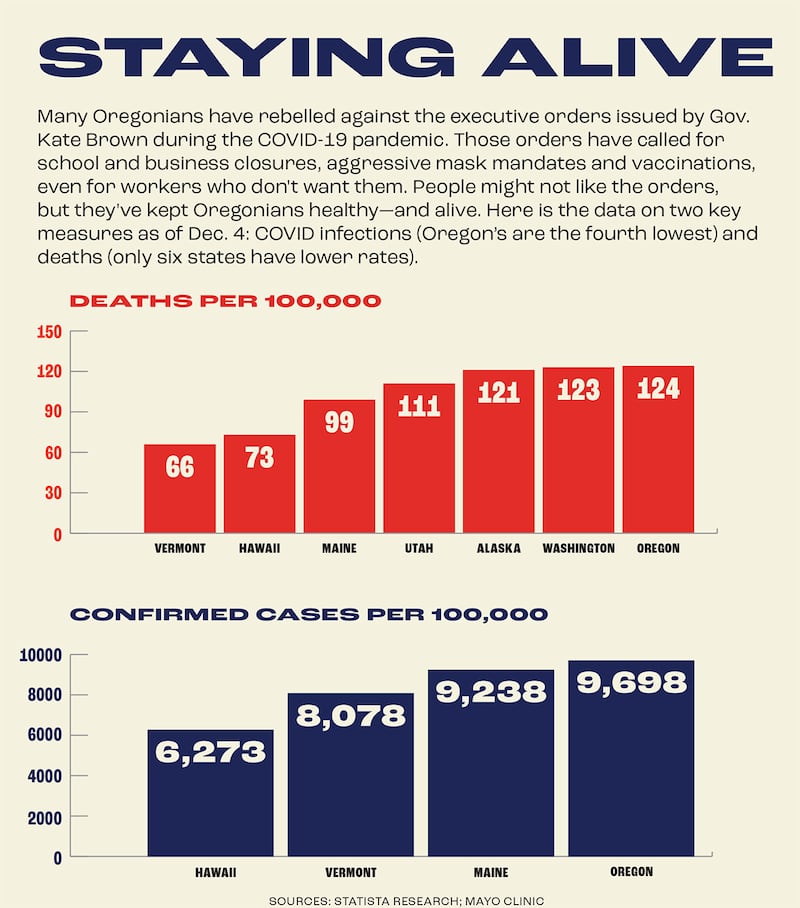

Perhaps most importantly, Oregonians contracted COVID less often and died from the virus at a far lower rate than residents of all but a handful of states during the pandemic (see “Staying Alive,” page 17).

“I have never seen a governor who accomplished so much, right from the beginning of her tenure, and who seems to receive so little credit for it,” says former Gov. Barbara Roberts.

Are Oregonians just more miserable than the rest of the country? Or does Brown’s lack of popularity reflect the unemployment checks people didn’t get, the school days their kids missed, and the homeless camps that flourished?

Politicos often referred to Ronald Reagan as the “Teflon president” because nothing bad stuck to him. For Brown it’s the opposite: She’s a blank canvas on which Oregonians sling all their frustrations. (She’s also created her own luck, as when she traveled to Washington, D.C., on Dec. 5 to pick up an award from Victory Fund, an LGBTQ political action committee, and was photographed without a mask, despite admonishing Oregonians to wear theirs at indoor gatherings.)

“The heart of the tragedy of Kate Brown’s tenure is that she is a truly kind, decent person who is impossible not to like personally,” says her former political consultant Kevin Looper, who also advised her predecessor. “The fact that she is so poorly regarded publicly is a deeper failure than just one person.”

In a brief interview, Brown attributes her unfavorable ratings to her efforts to challenge the “status quo.” She also blames the media, The Oregonian and Willamette Week in particular, which she says “peed all over me” for her COVID policies.

But she adds the polling doesn’t bother her.

“Frankly, I don’t give a damn,” she tells WW. “I want to focus on getting stuff done.”

We set out to figure out how a governor whose tenure has included so many high points finds herself rated so low.

We examined three theories:

She became Oregon’s COVID hall monitor.

COVID-19 defines Brown’s tenure like no other issue.

Even though Oregonians fared better than residents of most other states, Brown’s scattershot approach to the pandemic irked constituents.

From waffling initially on whether to order shutdowns to prioritizing vaccinations for teachers before seniors, some of her decisions have been head-scratchers.

And they had impact. For the first time since the Spanish flu, a governor’s day-to-day decisions affected Oregonians’ lives immediately: whether they could go to school or work; whether restaurants, bars, hair salons and coffee shops could open for business. Her decisions made a difference, every day, in every household.

To be sure, Brown can celebrate the outcome: Fewer people died per capita in Oregon than in all but a handful of states.

“She’s done a really good job on the COVID stuff,” says Len Bergstein, a longtime Salem lobbyist.

But Oregonians blamed her for the inconvenience and discomfort the pandemic caused—while few are running around cheering, “Kate Brown kept me alive!”

“The moment we’re in cannot be separated out from the pandemic,” says Melissa Unger, executive director of Service Employees International Union Local 503, the state’s largest public employee union. “Her opposition has made her the focus of everything. That builds its own narrative.”

Early in the pandemic, leading Democrats did not trust her to get the job done. Multnomah County Chair Deborah Kafoury and Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler launched public pressure campaigns to force Brown to move more aggressively to order Oregonians to stay home. Local school districts announced school closures before the governor did.

Brown often seemed reactive rather than projecting confidence. “I strongly approve of the way the governor handled the pandemic,” says political consultant Liz Kaufman. “But sometimes she climbs on things late or misses them entirely.”

Critics say Brown simply mimicked whatever Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and California Gov. Gavin Newsom did.

“I could anticipate how the governor was going to exercise her emergency powers by watching to see what California and Washington were planning,” says state Rep. Christine Drazan (R-Canby), who is running for governor. “And, you know, it might be tweaked a little bit, but she followed.”

To be fair, Brown made more targeted decisions than her peers on economic shutdowns: keeping construction firms and manufacturers open, for instance, when other states did not. And she reinstated an indoor mask mandate when the Delta wave arrived.

But there are still hard feelings from the economic inequities of Brown’s decisions.

Restaurant and hotel owners say it’s unfair they had to close while grocery stores and factories stayed open. Just as painful: changing and sometimes conflicting directives that made ordering supplies, scheduling staff and communicating with customers almost impossible.

“How could Gov. Kate Brown do better?” says Jason Brandt, CEO of the Oregon Restaurant and Lodging Association. “If the governor feels it’s in the public interest to reduce or close certain businesses for the sake of public health, then the government should compensate those businesses in the interest of the public good.”

That might sound crazy, but throughout the pandemic, Brown picked winners and losers. When she closed schools in March 2020, she decreed that no school employees should be laid off, giving them a kind of job security that evaporated overnight for waiters, hairdressers and other service industry workers.

Then, when COVID vaccines became available in 2021, Brown, unlike nearly every other governor, put teachers ahead of seniors—and then did not require them to return to schools. That fed into a narrative that Brown, who sprinkled her administration with former union officials, was beholden to the teachers’ union, a lousy negotiator, or both.

“In effect, her legacy will be ‘more people did not die,’ and that’s hard to articulate,” says Moore. “It’s hard to erect a statue to that.”

She lost people on the issues that matter most to them.

Few Oregonians will thank Brown for consigning them to their homes and locking their children out of school. Brown might have won more favor if state government had distinguished itself in crisis.

Instead, critics say she struggled with one of the governor’s core duties, managing state agencies.

Elected officials, particularly those in the same party, generally stay out of each other’s business. But on May 30, 2020, U.S. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) ran out of patience with Brown and the Oregon Employment Department. He demanded the director’s head.

That’s because more than 400,000 Oregonians had suddenly lost their jobs and the Employment Department could not answer its phones—let alone mail out unemployment checks. “This litany of incompetence and unresponsiveness has hit the breaking point,” Wyden said at the time.

Oregonians buried lawmakers with complaints. “I have never had as many calls for constituent help as when people were unemployed and couldn’t get their checks,” says Knopp. “I would guess 1,000 in my district.”

Brown forced Employment Department director Kay Erickson out that day. But another agency, Oregon Housing and Community Services, subsequently struggled mightily to find housing for residents of the 4,000 homes destroyed in 2020 wildfires and to get federal rent assistance checks to tens of thousands of Oregonians facing eviction this year.

“All that money that’s available, and they couldn’t get it out to people,” says state Sen. Lynn Findley (R-Vale).

“It’s completely unacceptable that thousands of Oregonians have been waiting longer than 6 months to get urgent rent relief,” adds State Treasurer Tobias Read, a Democrat running for governor. “I don’t see any sense of urgency, even the special session took over a month to organize. We need to treat this like the crisis it is—the money is there, this is an issue of making government work for the people, and right now it’s failing them.”

To be sure, every governor experiences agency failures. The Oregon Department of Transportation bought a $43 million communication system under Gov. Ted Kulongoski that didn’t work, and Gov. John Kitzhaber spent $200 million on an inoperable health insurance computer system. But no one went hungry, bankrupt or got evicted because of it.

When Brown’s agencies failed, the impact on individual Oregonians was tangible and immediate. The pandemic heightened the stakes of every agency screw-up.

On other issues important to Oregonians, Brown’s inability to make bold gestures proved a disappointment.

That was true on climate, where a decadeslong effort to pass cap-and-trade legislation on carbon emissions fizzled once again in 2019 and 2020, leaving Brown to impose an executive order that satisfied nobody.

“She’s had unprecedented revenue and a supermajority, but been hampered by a lack of clear direction and hamstrung by very serious communication issues,” says Looper, the political consultant. “Over time, this took away her ability to accrue credit for what has gone right, and increased the stickiness of what has gone wrong.”

The other issue that matters to a lot of people: Portland. And many people interviewed for this story say Brown’s poll numbers reflect widespread alarm about the state of Oregon’s largest city.

“People in Southern Oregon are pretty discouraged when they see Portland Police Bureau buildings on fire,” says state Rep. Duane Stark (R-Grants Pass). “Criminal justice reform should not equal anarchy.”

Andrew Hoan, CEO of the Portland Business Alliance, says Brown called regularly during the past 21 months to ask how she could be helpful to his members—then did nothing.

“If you are the CEO of Oregon Inc. and you look at the flagship city and see it in such distress, you intervene,” Hoan says. “That’s good government. As goes Portland so goes Oregon. This city is the state’s heartbeat.”

Hoan knows city and county governments are responsible for local issues, but he says the pandemic, political violence, and homelessness crisis have exceeded local resources.

“In every instance, there’s been a gap between her stated desire to help and the doing,” he says. “It’s absenteeism. It’s just an absence and it’s inexplicable to me.”

Some voters are sexist.

Brown has generated a cottage industry in bumper stickers and T-shirts: “Oregon Bigfoot Says ‘Fuck Kate Brown,’” “My Hate for Kate Keeps Me Warm,” and “If It’s Brown, Flush It Down.”

She’s survived five recall attempts, each a little more unhinged than the last.

Women governors are a rarity to begin with: Only nine states have one, and only 45 women have ever held to the top executive office in their states.

Brown is just Oregon’s second woman governor. Barbara Roberts, the first (1991-1995), noticed an interesting coincidence: Only two governors in modern Oregon history have faced recall efforts serious enough to reach the signature-gathering process. “Both are women,” Roberts says.

Many progressives say Brown’s approval ratings suffer because voters don’t trust or respect women leaders as they do men—and are possibly homophobic. (Brown, who is married to a man, Dan Little, identifies as bisexual.)

“There’s huge amounts of misogyny out there,” Kaufman says.

Former state Rep. Vicki Berger (R-Salem) says Brown doesn’t get the benefit of the doubt accorded her male predecessors, such as Kulongoski and Kitzhaber.

“To be a woman in politics is to dance an almost impossible dance,” Berger says. “We haven’t turned the corner on that.”

Berger says Brown hasn’t communicated a personal narrative like Kulongoski—orphan, Marine, union lawyer—or Kitzhaber—doctor, fisherman, Marlboro man—that would make her more relatable.

Roberts agrees. “I remember a picture of Ted Kulongoski fishing in the Deschutes River,” she says. “I rode a Brahma bull once. Kate Brown is a hiker, a kayaker and an expert equestrienne, but I don’t think people know that.”

Women in public office suffer from a “double bind” of often contradictory expectations, say researchers at the Barbara Lee Family Foundation, a Boston-based nonprofit that studies attitudes toward women in leadership.

“Women really have to walk a tightrope because voters want to see that women are strong enough,” says Amanda Hunter, executive director of the foundation. “But then, if women are strong—and we’ve seen this during COVID—they can face a backlash because voters think they’re too tough.”

Horvick the pollster says his numbers show less sexism than Brown’s admirers might think, in that Brown’s approval numbers are not that different between men and women: 32% of men approve of Brown and 33% of women do.

“Men are a little bit more negative towards her than women are, but it’s usually within just a few points,” adds Horvick.

Brown’s four Democratic predecessors all saw their popularity plummet toward the end of their tenures. Gov. Roberts left office with numbers lower than Brown’s—without a pandemic.

The good news for Brown: Roberts today is the gold standard for Democrats, a beloved figure whose endorsement candidates covet. She attributes her rebound to crisscrossing the state in a wide variety of roles in retirement. The better people know her, the more they like her.

“I don’t think Oregonians have seen the person Kate is,” Roberts says. “That doesn’t help your polling numbers.”

The question for 2022, of course, is how Brown’s unpopularity will shape a competitive Democratic primary and a likely three-way race for governor in November.

Nationwide, Democrats face a challenging 2022. And barring an unforeseen rally in Brown’s popularity, she will be a dead weight on them.

In a normal year, Kotek, the longest-serving House speaker in Oregon history, would be a strong favorite for the party’s nomination, given her record of accomplishment and support from labor unions that dominate Democratic primaries. But with Republicans and state Sen. Betsy Johnson (D-Scappoose), who is running as an independent, likely to brand Kotek as Kate Brown 2.0, the speaker is vulnerable. (Kotek declined to discuss Brown’s weakness. “Tina is not interested in playing Monday morning quarterback,” says her campaign manager, Thomas Wheatley.)

Republicans are in an uproar over vaccine mandates and shutdowns.

And the people in the middle, the less engaged voters? They are the poll respondents who sent the governor’s numbers cratering.

“The first four years of her term, you had a chunk of voters—somewhere between 20% and a third—who basically had no opinion about her,” says Horvick. “Over time, anybody who was undecided about her—a lot of those are not affiliated voters—have become negative towards her.”

Similar dynamics upended the Virginia governor’s race last month and, in Oregon, have opened the door for political newcomer Nicholas Kristof in the Democratic primary, generated strong fundraising for Johnson the independent, and even prompted the GOP’s Drazan to cut short a promising legislative career to attempt something no Oregon Republican has done since 1982—win a governor’s race.

On Dec. 3, the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, a highly regarded national online newsletter, noted the 2022 environment for Democrats looks dicey.

“Democrats may be glad that Gov. Kate Brown is term-limited,” the publication wrote. “This is shaping up to be a unique race with interesting dynamics, and we are shifting it from ‘Solid’ to ‘Likely Democrat’ at this time.”

It is perhaps telling that Brown has shifted her election-year gaze to other states, rather than boosting her own popularity.

“I could be out there raising money so that I could be running ads,” she says. “I am choosing not to do that. I am raising money. I’m just doing it for other people: the women governors across the country, like Gretchen Whitmer [of Michigan] and Laura Kelly [of Kansas], who are going to have the most difficult reelection bids of their lives.”

Staying Alive

Many Oregonians have rebelled against the executive orders issued by Gov. Kate Brown during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those orders have called for school and business closures, aggressive mask mandates and vaccinations, even for workers who don’t want them. People might not like the orders, but they’ve kept Oregonians healthy—and alive. Here is the data on two key measures as of Dec. 4: COVID infections (Oregon’s are the fourth lowest) and deaths (only six states have lower rates).