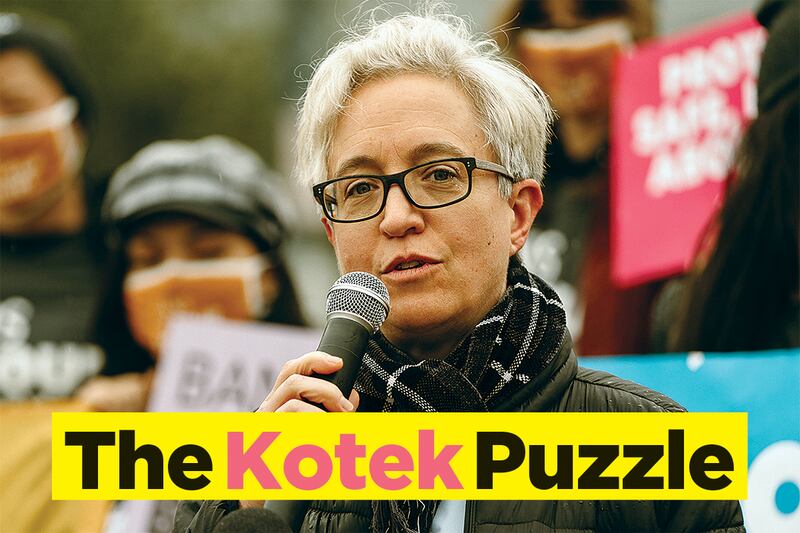

With less than two months to go until the May 17 primary, Tina Kotek is the Democratic front-runner to be Oregon’s next governor.

Yet she faces an unusually challenging path to an office her party has held for nearly four decades.

As the longest-serving speaker of the Oregon House, Kotek, 55, delivered on an ambitious agenda with steely efficiency.

But for some reason, nobody who’s done the job Kotek now seeks is endorsing her. Nor is her counterpart in the Senate.

Not former Govs. John Kitzhaber, Ted Kulongoski or Barbara Roberts. Not Senate President Peter Courtney (D-Salem), who led the Legislature alongside Kotek since 2012. (Kitzhaber and Roberts have endorsed State Treasurer Tobias Read, Kotek’s chief opponent in the primary. The others are staying on the sidelines.)

And all are Democrats.

Of that group, only Roberts would discuss her reasoning.

But interviews with legislators, staffers and lobbyists—people who love and fear Kotek—reveal a complex portrait of a formidable operator and help explain why some Democrats feel uneasy about her.

For many elected officials, the best way to succeed is to do little and advance through attrition.

Not Kotek. Under her leadership, House Democrats won passage of a progressive wish list ranging from a minimum-wage increase and health care for nearly all to criminal justice reform and the nation’s most aggressive housing legislation.

Kotek led the way in a calculating, sometime ruthless fashion, pushing hard to the left. Her success made her both the favorite of most progressive interest groups and perhaps Oregon’s most beatable Democratic front-runner for governor in decades.

The prospect of challenging Kotek enticed the most formidable unaffiliated candidate in 90 years—former state Sen. Betsy Johnson (D-Scappoose)—and an unheard of 19 GOP contenders to enter the race.

Here’s what makes Kotek effective—and vulnerable.

SHE CUTS DEALS

During her tenure as House speaker, Kotek successfully engineered an ambitious agenda with the precision of a Swiss watchmaker. She passed massive new taxes, yes—but also pushed the envelope on abortion, housing, the environment and workplace laws.

“She’s been a very strong and very effective speaker,” says former Senate President and Secretary of State Bill Bradbury. “She’s shown over a long period of time that she can deliver on key Democratic priorities.”

Kotek has been so effective in part because of her willingness to cut deals.

After a failed attempt to raise Oregon’s minimum wage in 2015, Kotek agreed to a compromise that some Democrats opposed: lower minimum wages for rural Oregon. The bill passed in 2016.

And in 2017, Democrats passed the biggest single tax increase in state history, a massive $5.3 billion transportation funding bill, with significant concessions to Republicans, such as a new rail terminal near Ontario and the widening of Interstate 205 near West Linn.

“The transportation package in 2017 was incredibly difficult,” says Oregon Labor Commissioner Val Hoyle, who was then House majority leader. “It was something that people didn’t think we would be able to pass.”

Kotek’s partisan rivals appreciated her pragmatism.

“No speaker can be effective without being transactional,” says former House Minority Leader Mike McLane (R-Powell Butte), who often battled Kotek. “I counted on that. I needed her to be that way.”

But the dealmaking that clinched the most consequential bill of Kotek’s career required her to betray a central segment of her party’s base: public employee unions.

In 2019, Kotek spent months navigating between business interests, who wanted to scale back the state’s underfunded Public Employee Retirement System, and progressives, who wanted a big corporate tax increase for schools, called the Student Success Act.

She was able to achieve both, even though it meant strong-arming Democrats, including Reps. Mitch Greenlick (D-Portland) and Andrea Salinas (D-Lake Oswego)—who came to the House floor in tears after Kotek “persuaded” her to vote yes on the pension cuts.

“There’s no way that the Student Success Act would pass without [the PERS cuts],” says then-state Rep. Alissa Keny-Guyer (D-Portland). “I give Tina huge kudos for standing up to the labor unions. They made it incredibly painful for all of us who voted for the bill.”

That grudge persists.

“Some of our folks are still really upset about that vote,” says Joe Baessler, political coordinator for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Council 75, which joined the United Food and Commercial Workers in not endorsing Kotek in the May primary.

Kotek says when she made hard choices, it was always for better outcomes.

“I bristle at the word ‘transactional’ because it does seem to imply that you’re making choices to get things done that aren’t good choices,” she says. “When people ask for things and I think they’re a bad idea, I don’t do them.”

Kotek’s transactional nature also cost her the support of former Gov. Roberts, who for years has bestowed the individual endorsements most coveted by Democrats.

Roberts says she’s backing Read because of the broad perspective he gained in six years as a statewide official. But her choice rekindled chatter about what both women acknowledge is some “history.”

In 2017, Special Olympics Oregon needed a financial bailout. Roberts, a longtime supporter of the organization who left office in 1995, approached Kotek for help.

The conversation went badly. According to people familiar with the exchange, Kotek said she’d consider an appropriation, but only if Roberts would help convince a reluctant Democratic lawmaker to support a crucial housing bill. That annoyed the ex-governor, who left Kotek’s office empty-handed.

“To be honest, I had had a long day,” Kotek recalls. “I made a flip comment that she mistook as transactional. It was not. And I thought we had lunch and made up and had resolved our conflict.”

SHE IS VERY LIBERAL

During the course of Kotek’s tenure, Democrats consolidated power and moved aggressively on such measures as granting driver’s licenses and publicly funded abortions to undocumented immigrants and one of the nation’s most aggressive green energy mandates. They also passed statewide rent control and abolished single-family residential zoning—first-in-the-nation policies aimed at relieving the state’s housing crisis.

Such policies played well in deep-blue Portland. “She’s done more than any other leader in the state, maybe the country, on housing and homelessness,” says Keny-Guyer, who represented a liberal Southeast Portland district.

But some Democrats say Kotek’s prioritization of social justice and environmental issues put her to the left of the average voter in a statewide race.

In 2021, Kotek was chief sponsor of House Bill 3115, which enshrined in state law the right to camp in public spaces—over pushback in Salem from critics who saw the bill as exporting Portland’s policies to the rest of the state.

In 2018, Kotek abruptly removed a longtime moderate as chair of the House Judiciary Committee—Rep. Jeff Barker (D-Aloha)—to achieve a top progressive priority: criminal justice reform, including the abolition of Oregon’s death penalty.

“We used to get along well,” says Barker, a retired Portland police lieutenant and ex-president of the Portland Police Association. “We were very aligned on abortion and organized labor. I supported her for speaker, and she came out to my house for dinner.”

But Barker opposed lawmakers overturning the death penalty without a vote of the people. (The public had approved the death penalty with a 1984 ballot measure.) So Kotek yanked Barker’s gavel as chair of House Judiciary Committee, a position he had held for 15 years. “I was shocked,” says Barker, who retired from the Legislature in 2021.

Barker was “not interested in entertaining criminal justice reform in a moment where we had to have different conversations,” Kotek says. “And so Jennifer Williamson took over.”

And in the 2019 session, Williamson and Senate Judiciary Chair Floyd Prozanski (D-Eugene) effectively ended the state’s death penalty.

“As we gained more seats, she went back to her true philosophical positions,” says former state Rep. Brian Clem (D-Salem), who served with Kotek for 15 years. “She started her career as a lobbyist for hungry kids, and she went back to her roots—progressive activist Tina.” (See “Hammer of the Gods,” below.)

SHE DOESN’T ALWAYS KEEP HER WORD

The two most common criticisms of Kotek—that she’s too pragmatic and at the same time too liberal—don’t really square. What kind of inflexible leftist ideologue cuts a deal that outrages public employee unions?

What the two conflicting characterizations reflect is how often Kotek got what she wanted, and how many egos she left bruised in the process. Like Michael Jordan on the basketball court, she’s more revered than loved—because she would do anything to win.

“If you are in her way,” McLane says, “you are going to be roadkill.”

Supermajorities in her last two sessions as House speaker gave Kotek the power to dictate terms. She wasn’t shy about using it. Over time, Kotek gained a reputation as a politician for whom the ends justified the means.

“I don’t think that’s a very helpful way to learn leadership—to have absolute power,” says Roberts. “I just don’t think it’s healthy.”

Some adversaries she bested even feel she lied to them.

In January, she alienated state Rep. Janelle Bynum (D-Clackamas), one of the state’s few Black lawmakers. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, Bynum led her colleagues in passing a package of police reform measures. Afterward, she told Kotek she thought it was time for a person of color to be House speaker.

Bynum left the conversation believing Kotek had pledged to support her for speaker in the future if Bynum didn’t mount a bid to challenge Kotek for the post in 2021.

It didn’t work out that way. After Kotek announced she would run for governor, Bynum put her name forward as a candidate for speaker. But the Democratic caucus that Kotek ran with iron discipline for almost a decade fell in behind now-Speaker Dan Rayfield (D-Corvallis) instead. Bynum told WW at the time she felt betrayed.

Kotek says Bynum (who declined to comment for this story) misunderstood Kotek’s intentions. “I believe she’s a strong leader, and I have a lot of respect for her, but I don’t believe I made the commitment that she thinks I did,” Kotek says.

In 2021, Kotek irked Democrats in April when she gave Republicans an equal say in the once-per-decade process of redistricting to keep the GOP from blowing up the session.

Then, in September, Kotek infuriated Republicans by reversing herself and telling House Minority Leader Christine Drazan (R-Canby) she was changing the deal to give Democrats a majority on the panel drawing congressional maps.

“They didn’t hold up their end of the bargain,” Kotek says. So, having convinced Republicans not to block their agenda, Democrats now got the congressional district maps they wanted too.

Former state Rep. Margaret Doherty (D-Tigard), whose gavel as chair of the House Education Committee Kotek yanked in 2020, says the Bynum and redistricting episodes reflect Kotek’s willingness to say anything to get what she wants.

“I worked with both of them [Kotek and Read],” says Doherty, a retired teachers’ union official who served with Kotek for a decade, “and I’m endorsing Tobias because I want somebody in that office who has integrity.”

The ultimate question about Kotek is whether the longest-serving speaker of the House in Oregon history has made the state better.

Some indicators, such as K-12 test scores, the housing shortage, and inadequate provision of mental health services, suggest the state remains deeply troubled.

Portland pollster John Horvick of DHM Research says Kotek is the “strong front-runner” for the Democratic nomination but also notes that Oregon voters’ unhappiness has reached historic levels. “We’re seeing the most negative numbers Oregonians have expressed in the past 30 years,” he says.

“We are a high-tax state with low services,” adds former state Rep. Jules Bailey (D-Portland), who is endorsing Read. “Shit’s not working.”

Opponents label Kotek “Kate Brown 2.0,” hoping Brown’s low approval ratings will taint Kotek.

Both are Portland liberals who emerged from legislative leadership, both identify as LGBTQ+, and both have held power as Oregon descended into its current funk.

But Brown is endlessly consultative. Kotek, by contrast, moves decisively. “Their leadership styles are wildly different,” says Felisa Hagins, political director of Service Employees International Union Local 49, whose members back Kotek.

Kotek is less outgoing and more liberal than Brown—and perhaps more focused on an agenda and clear-eyed about Oregon’s problems.

She concurs with Bailey’s assessment that “shit’s not working.”

“I agree,” Kotek says. “I don’t think things are working the way they should be working.”

Of Democrats’ major accomplishments on her watch, Kotek says increases in the minimum wage have made a substantial impact, benefitting hundreds of thousands of Oregonians. Other victories—including the Student Success Act, statewide zoning changes and $1 billion in new funding for housing, and a half-billion dollars in new money for mental health services—will take more time to show results.

Yet Kotek is on the ballot now—not when those results arrive.

She blames COVID-19 for much of the state’s malaise. “Prior to the pandemic, we had the biggest economic numbers we’ve ever seen,” Kotek says. “We were bringing prosperity to more parts of the state, and then the pandemic hit.”

COVID-19 exposed underinvestment and poor management at the Oregon Employment Department and other state agencies. Kotek says if she were to be elected governor, the skills that made her an effective speaker would make the state function better.

“To treat me fairly, people should look at my record,” she says. “My job was to make sure the Legislature functioned and pass important legislation. And I think anybody who is going to be honest will say, that’s an A+.”

Hammer of the Gods

To all but a few intimates, Tina Kotek remains a cipher.

Tina Kotek steered legislation through the Oregon House with the same no-drama efficiency that she’s piloted a 2004 Honda Civic—methodically—to Salem since first winning election in 2006.

The vehicle now has 250,000 miles on it. State Rep. Barbara Smith Warner (D-Portland), Kotek’s top deputy for four years, says it’s still in mint condition. “You could eat off the floor of that car,” Smith Warner says.

When the two traveled together, however, Smith Warner always drove.

“Tina will not go a mile over the speed limit,” Smith Warner says. “She’s a very cautious driver.”

Of the triumvirate that ran Salem, Gov. Kate Brown is known for her bubbly, warm nature, Senate President Peter Courtney (D-Salem) for his emotional style and reverence for tradition, and Kotek for her steely, robotic efficiency.

Kotek calls herself a “private person” and an introvert. She’s most comfortable sipping unsweetened Lipton black tea in her office with a small inner circle (mostly long-term staffers and labor leaders) or road-tripping around the state with colleagues, Prince or Abba on the stereo, a bag of Swedish Fish at the ready.

She grew up in York, Pa., a blue-collar town of 45,000 about 85 miles southwest of Philadelphia. (Kotek always kept a supply of York Peppermint Patties in her House office.)

In high school, Kotek played three sports, edited the yearbook and school newspaper, and graduated second in her class.

Kotek began college at Georgetown, but as an emerging lesbian from a working-class town, she says she felt out of place at the elite Catholic school.

A foray in commercial diving left her with a damaged ear and unemployed. She then worked as a travel agent for two years and enrolled at the University of Oregon in 1990, earning a degree in religious studies.

After finishing her master’s in international studies and comparative religion at the University of Washington in 1998, Kotek moved to Portland and worked first as an advocate at the Oregon Food Bank and, after that, for Children First for Oregon.

In 2005, she and her now-wife, Aimee Wilson, bought a modest, 1,089-square-foot home in Kenton where they still live. A lapsed Catholic, she now attends an Episcopal church and for years was part of a Capitol prayer group along with former House Minority Leader Mike McLane (R-Powell Butte) and others.

The district she represented, HD 44, a working-class area that includes Kenton and St. Johns, contains fewer Republicans than all but two of the state’s 60 House districts.

Kotek loves her dogs, Rudy and Teddy, and will sip the occasional bourbon (Portland’s Freeland is her favorite). She loves watching superhero movies in a darkened theater with a small group of friends, all of whom often wear T-shirts promoting the films they watch (Kotek particularly likes Thor: Ragnarok and kept a Captain America shield in the speaker’s office).

“Once I got into office, my moviegoing was escapism,” Kotek says. “So thank God, Marvel decided to make a whole bunch of movies.”