On a warm and sunny Wednesday afternoon just outside Oregon Health & Science University’s Primate Research Center in Beaverton, disgruntled workers protested what they say are low wages and forced overtime due to short staffing—a recipe, they say, that could result in dead monkeys.

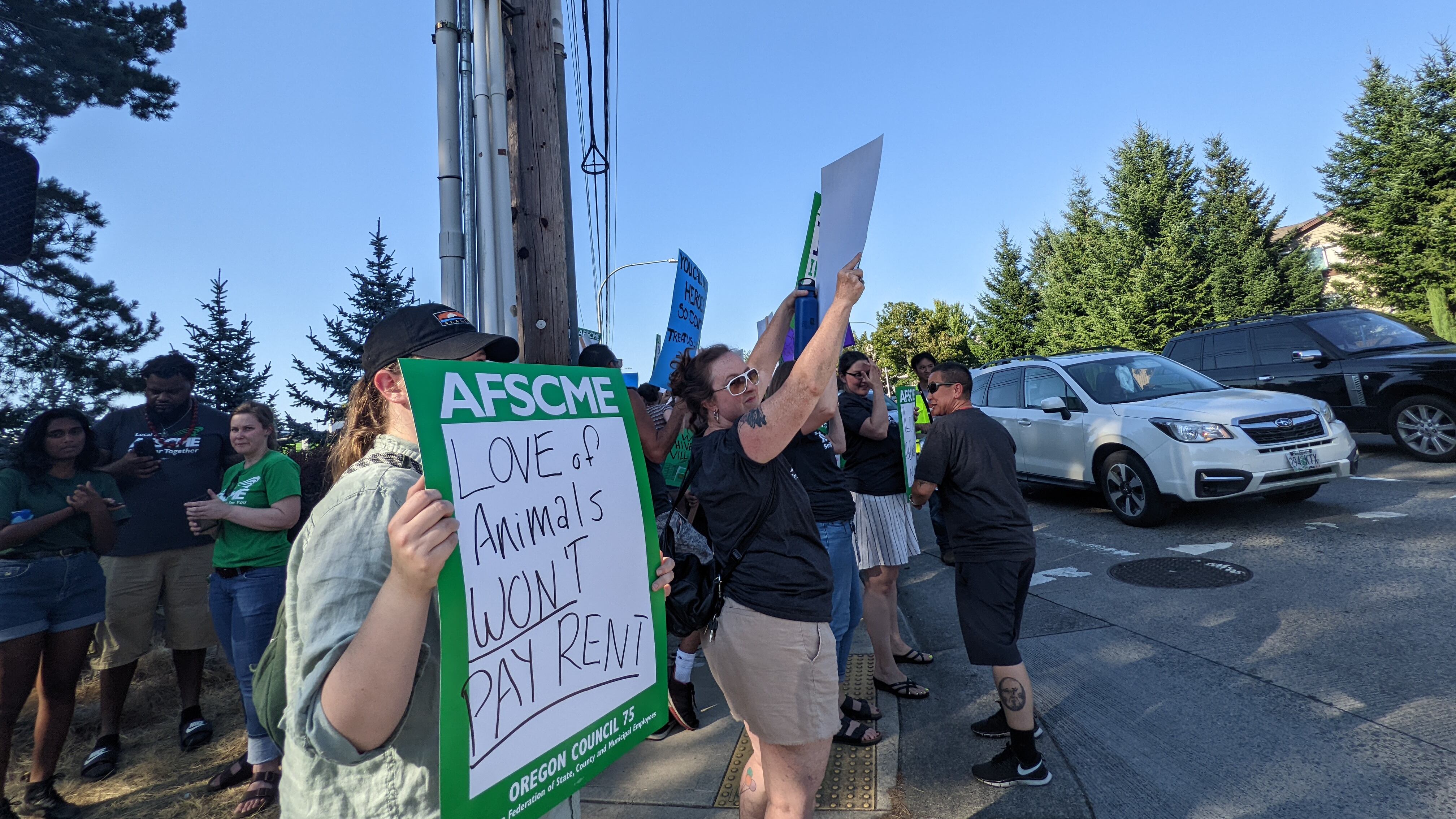

For years, animal rights activists have decried the Oregon National Primate Research Center. But the Aug. 24 demonstration revealed a newly aggrieved party: the monkeys’ caretakers.

Staff at the center care for nearly 5,000 primates bred at the 200-acre site. The monkeys are used to conduct research into subjects such as how marijuana use impacts fertility and to test the effectiveness of new HIV treatments. Staff are responsible for taking care of the primates and ensuring experiments go smoothly, down to giving the monkeys their daily dose of THC.

Angela Calabrese, an employee at the center for nine years, told WW: “We’re so short staffed, everyone’s burnt out. We can’t get new people in the door because the starting wage is so low. It’s not competitive. We can’t keep people that have been here long term, because there’s better offers elsewhere. We’re just sort of dwindling.”

Calabrese says she often works 12 hours a day despite her eight-hour-a-day contract.

“We’re all expected to do 12 hours of work in an eight-hour day,” she says. “And it’s just not sustainable.”

OHSU spokeswoman Sarah Hottman tells WW that “the picket was related to staffing levels at the [monkey sanctuary] rather than the contract” and that OHSU leaders are “actively working on short- and long-term solutions to bolster staffing levels and support the well-being of our members.”

The monkey sanctuary laborers—who care for baboons, squirrel monkeys and macaques—are only the latest group of OHSU workers to protest what they see as unfair working conditions.

OHSU has been bargaining since March 8 with the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 328, which represents over 7,000 workers at OHSU and many of the sanctuary workers. Members are currently voting whether to authorize a strike.

“So far, OHSU has not made the adjustments to actually fix the situation, and for close to two years now, the West Campus has been ringing the bell to say, hey, we are at crisis level,” says Ross Grami, program manager for AFSCME Local 328. “The larger institution at OHSU has not been listening, including to listen to the management out at the West Campus.”

Haley Wolford Davis, another worker at the sanctuary, says workers’ feelings for the monkeys are being exploited for OHSU’s benefit, telling WW that their “compassion and their commitment to their animals shouldn’t be used against them in order to accept low wages and burnout.”

Many animal care staff at the picket were concerned that short staffing could result in fatal accidents like the one last year that led to the deaths of two monkeys.

“When you have a staff that’s burned out and stretched so thin, when does the mistake happen? It’s not a misplaced file. It’s an animal that’s gets harmed or killed. It has much higher stakes, and no one wants that level of responsibility for less than $16 an hour,” says Gregg VanFleet, an employee at the center for 14 years.

Picketers standing in the shade continually pressed the crosswalk button for about an hour, forcing motorists to stop and watch as picketers cheered and waved signs. Occasionally, an angry driver would start honking at the crowd, attracting even louder cheers in response.