Oregon Secretary of State LaVonne Griffin-Valade determined in a report released Monday afternoon that a state audit of the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission, which was embroiled in a political scandal that culminated in the resignation of former Secretary of State Shemia Fagan in May, should be held in as high regard as any other audit the state’s Audits Division has conducted.

Griffin-Valade’s determination to keep the audit up, and unchanged, comes in direct opposition to the findings of a California firm hired by Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum this spring, which recommended that the state remove the audit from its website because the independent firm determined that audits staff repeatedly failed to address potential threats of independence posed by Fagan’s involvement in the audit early on.

“There’s no doubt public confidence was shaken by the former Secretary’s actions,” Griffin-Valade wrote in a statement Monday. “However, the public interest in this case is best served by independent auditors providing evidence-supported recommendations to state government. Neither my review nor any other has uncovered a reason to think this report is anything short of that standard. For that reason, I encourage the auditee and other state leaders to treat this report with the same high regard they do any other report from the Oregon Audits Division.”

A spokesman for Rosenblum said on Tuesday that her office “stand[s] by the Sjoberg report and its recommendations.” The state paid the firm $138,000 for its report.

Gov. Tina Kotek did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

As WW reported this spring, records show that Fagan repeatedly pushed staff within the Audits Division to talk to cannabis chain owner Rosa Cazares, a top campaign donor to Fagan, while determining the scope of the OLCC audit. Records also showed that Cazares provided feedback on the description of the audit scope to Fagan—calling into question the audit’s independence. It was not until after the audit was in its final form this February that Fagan officially recused herself from it as she prepared to go to work for Cazares and her cannabis dynasty, La Mota, as an independent contractor making $10,000 a month for research on cannabis regulations in other states.

Fagan resigned five days after WW reported on her contract with La Mota. Soon after, Rosenblum hired the California firm Sjoberg Evashenk Consulting to conduct an independent review of the audit. (Disclosure: Rosenblum is married to the co-owner of WW’s parent company.) The firm recommended in October that the Secretary of State’s Office remove the audit from its website “and perform additional audit work.”

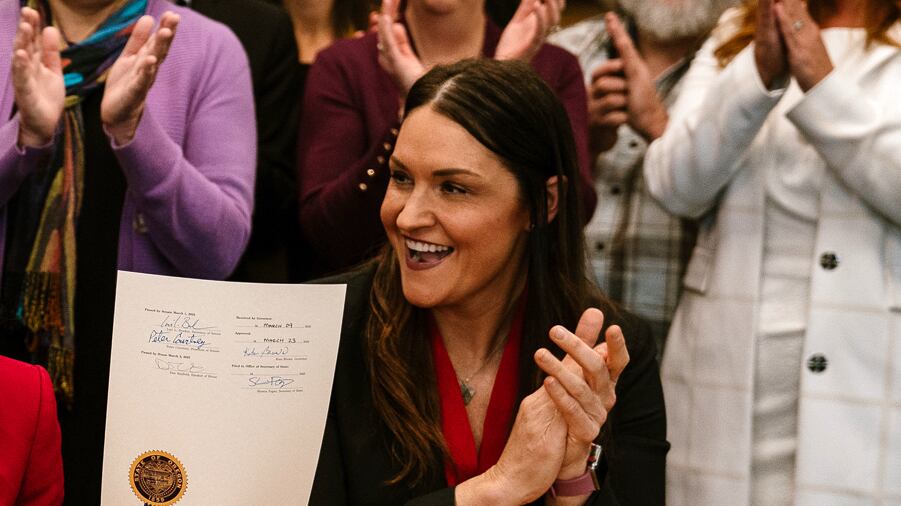

Griffin-Valade, however, did not take down the audit. And she released the report on Monday saying that she believed in its integrity.

“My review determined that the report would not have changed if the auditors were aware of the threat to independence when conducting their work,” Griffin-Valade wrote. “The audit report relies on hundreds of work papers, more than 30 stakeholder interviews, state and federal laws or memos, and data from the audited agency. It does not rely on any materials related to the former Secretary or La Mota.”

Griffin-Valade did, however, implement a number of changes to the state’s audit process in response to this particular scandal. The secretary of state will no longer take part in “scoping” meetings the Audits Division convenes before launching an audit to determine what, and whom, the audit should focus on. (It was during such meetings that Fagan pushed auditors to speak to Cazares.) Griffin-Valade also pledged that the Audits Division would “go further to strengthen its independence policy” and undergo a new process to decide whom audits staff should interview.

Griffin-Valade added in her report: “It’s worth noting that after reading pages and pages of media reports on the audit, I can’t find one instance where a fact in the report’s findings is convincingly questioned.”