Climb to the top of the Astoria Column, the imposing tower perched on Coxcomb Hill high above the city, and look northwest. On a fine day, the mighty Columbia stretches to the horizon, a smooth gray immensity. Goliath container ships glide placidly upriver, while the looming forests of the Washington shore recede into mist. The graceful arc of the Astoria bridge wraps the peaceful scene in a bow; the river glitters with promise.

Don’t be fooled. You’re looking at a monster.

The mouth of the Columbia is one of the most fearsome stretches of water in the world, known for centuries as the “Graveyard of the Pacific.” By one estimate, more than 2,000 ships have been wrecked here since record keeping began in 1792. The reason, according to Captain Mark Hails, who is based in Astoria, is simple: the convergence of four elemental forces—wind, waves, tides, and currents—creating a vortex of energy that poses unique dangers to shipping.

Hails is a Columbia River Bar pilot, a highly trained expert at guiding container ships and other giant vessels through the waters that swirl around the sand that guards the river’s mouth. Inbound or outbound, when ships need to cross the bar, they rely on Hails and his 14 fellow pilots to take command of the bridge and steer a safe passage.

The hazards are the stuff of legend: breakers 40 feet high, howling winds, relentless currents, and treacherous tides. To maintain control of the vessel, pilots have to balance these vectors with the precision of a gymnast executing a double backflip. “The problem is that each force pushes a ship in a different direction,” Hails says. “That’s what makes this so crazy.”

The Columbia is big by any standard: It drains an area of a quarter-million square miles, including most of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, and much of Montana, British Columbia, and Alberta. What makes it so dangerous is its unusual geometry. Most big rivers terminate in deltas, where the river splits into hundreds of distributaries, like a fraying rope. The Amazon, the Mississippi, the Nile, and the Mekong have deltas that are hundreds of miles wide, dissipating the flow.

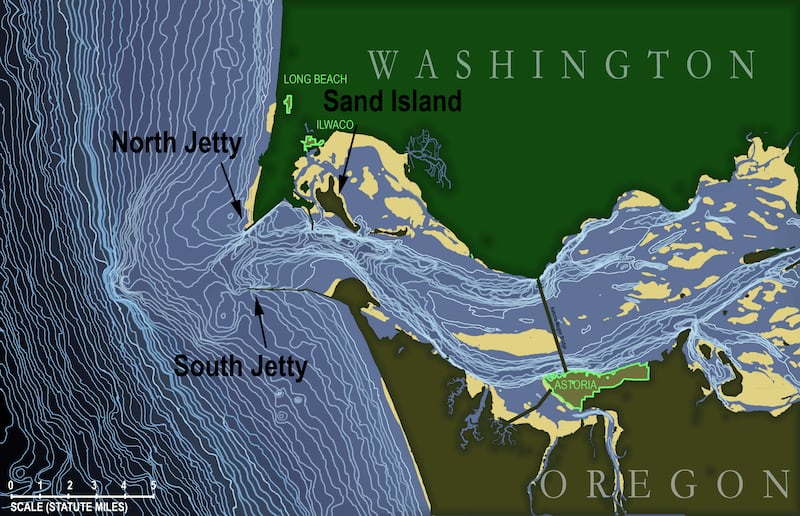

The Columbia is different. Hemmed in by implacable basalt cliffs, the water is confined to a single channel. Making matters worse, it narrows at the mouth, where Clatsop Spit in Oregon and Washington’s Cape Disappointment come together like a carpenter’s vice. Following Bernouilli’s Law, which states that a fluid flowing through a constriction will accelerate, the river picks up speed and comes blasting through the mouth with unmatched fury, throwing about 7,500 tons of water at the Pacific Ocean every second.

“It’s like putting your thumb on a garden hose,” Hails says. “There aren’t many rivers in the world with a current that strong.”

As the current speeds up, it dumps sediment on the ocean floor, forming a kidney-shaped sandbar a couple of miles offshore. This bar triggers the opposing force—the Pacific swell. Waves born off Japan’s coast grow in strength as they travel across the Pacific, gaining momentum from ocean storms. When they encounter the sudden shallow water at the bar, they break and detonate, hurling their pent-up energy straight into the swift river current. Throw in the unpredictable effects of storm winds and turning tides and you unleash the monster.

Trying to Tame Nature

“Mere description can give little idea of the terrors of the bar of the Columbia,” said Captain Charles Wilkes, whose sloop, the USS Peacock, was shipwrecked near Astoria in 1841. “All who have seen it have spoken of the wildness of the scene, and the incessant roar of the waters, representing it as one of the most fearful sights that can possibly meet the eye of the sailor.”

With its constant shifting, the bar claimed so many ships that Congress intervened. In 1884, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction on a massive jetty to protrude into the Pacific from Clatsop Spit. A second jetty was added in 1914. The jetties were designed to concentrate the flow of the river like a firehose, scour the riverbed, and push the bar away from the mouth.

The jetties helped—today the bar is more stable and lies farther offshore—but hardly tamed the monster. Crossing the bar is still perilous, especially for marine giants like container ships. These vessels need deep water—about 43 feet of draft. The only safe passage for them is to stay true to a narrow shipping channel that runs along the deepest course of the river, which is 600 feet wide. If they stray into shallower water, they risk running aground on the riverbed and getting spun like a pinwheel. That’s more or less what happened to the Ever Given, which got stuck like a chicken bone in the Suez Canal in 2021, or the MV Dalí, which demolished Baltimore’s Key Bridge earlier this spring.

Given a couple of million years, geologists predict the Columbia will settle down and develop a delta. In the meantime, let’s treat the river with respect. It is a phenomenal force whose true depth lies hidden beneath the surface.

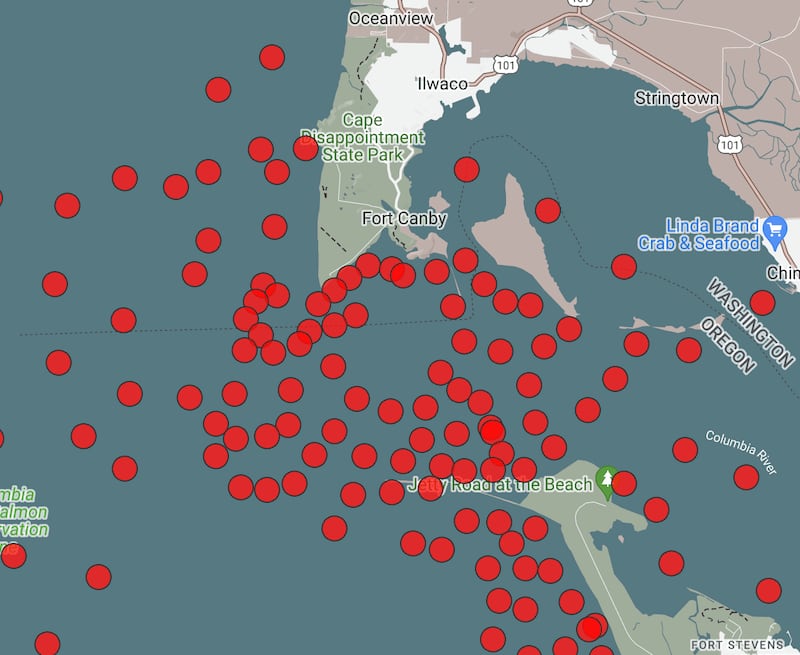

This story is part of Oregon Summer Magazine, Willamette Week’s annual guide to the summer months, this year focused along the Columbia River. It is free and can be found all over Portland beginning Monday, July 1st, 2024. Find a copy at one of the locations noted on this map before they all get picked up! Read more from Oregon Summer magazine online here.