Love them or hate them, it’s not just your imagination: Portland’s crow population has exploded.

Gary Granger—who readers may remember from his 2019 corvid conversation with us and his report of an assault on a homeless man that a 911 dispatcher downplayed—and his research partner, Rebecca Provorse, count crows between November and February throughout downtown Portland. They define that as anywhere west of the Willamette River and east of Interstate 405′s carved borders (the Pearl District and Old Town fall within this boundary, for example, but Goose Hollow does not). The Oregon Birding Association published Granger and Provorse’s findings for the autumn 2023 issue of its biannual journal Oregon Birds.

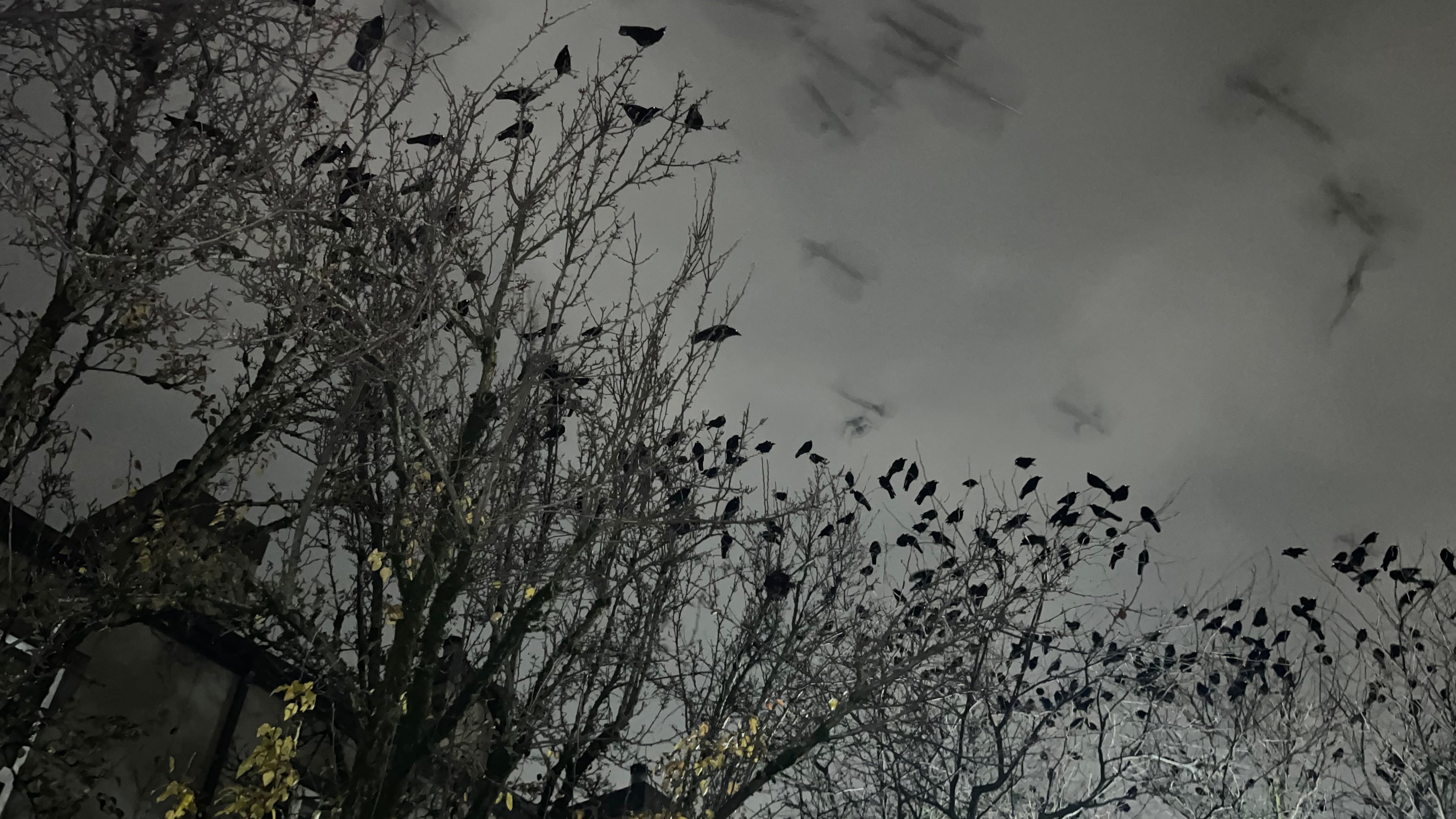

Should this year’s trends continue, Portland’s murder rate will steadily climb past the tens of thousands. Five key findings from Granger and Provorse’s report stand out as sunset squawking grows louder and earlier.

Downtown Portland’s crow population has tripled in less than a decade.

Crows caught Granger’s and Provorse’s eye during the winter of 2012–13: 1,000 crows were logged near Portland State University by other researchers that winter. After their first study in the winter of 2017–18, Granger and Provorse logged over 7,000 crows in the aforementioned downtown area. Last winter, they counted more than 22,000 crows in January. Put another way, crows outnumber students on Oregon’s third largest university campus by more than 1,000, according to PSU’s 2023–24 student body count of 21,040 between all graduate and undergrad programs.

Crows roost in some of Portland’s least secure locations.

Crows seem to prefer every kind of tree except evergreens (there goes the Christmas crow decoration market). More than 700 can fit on a barren tree, with several crows perched on even the spindliest branches. Crows also congregate in areas with seemingly little protection from predators, like on open lawns or in empty parking lots. Of all Portland’s bridges, crows also seem to favor the Hawthorne Bridge the most, perching on its superstructure frequently. Granger and Provorse also noted that when perched on roofs, crows place themselves on the farthest edges of the building.

Downtown Portland’s roosts defy logic.

Along with choosing exposed lawns, outer tree branches, and precarious roof perches, crows don’t pack closely enough together to offer one another the benefit of body heat. They also don’t seem territorial: Granger and Provorse have never seen crow turf wars. They also noted that while the crow population’s strength in numbers isn’t entirely unusual, it is strange for so many birds to prefer roosting above busy streets.

Portland Metro Chamber’s hawk hazing program hurts more than it helps.

Bird poop is gross at best and, being slippery when wet, dangerous at worst. Portland Metro Chamber—fka the Portland Business Alliance—started releasing Harris’ hawks in 2019 to haze the local crow population, which that winter had jumped from a high of nearly 15,000 birds to over 18,000. Though the hawks are disruptive, they don’t eat crows. Granger and Provorse observed crows returning within hours to areas from which hawks had chased them. (Before anyone calls for crueler and deadlier birds of prey, lethal efforts used in rural areas could be why crows now flock to the concrete jungle.) But the hawks are just disruptive enough that Granger and Provorse can’t observe the crows’ uninterrupted behavior. If they could, the researchers might get closer to answering questions within their study, like why Portland of all places is so attractive, or why crows choose areas thick with cars and people.

Portland’s crows present rebranding opportunities.

Should another nearby location become more attractive, crows could eventually get their flock out of downtown Portland. Granger and Provorse note a 1997–2009 effort by the University of Washington to restore Bothell’s North Creek Wetlands. When saplings were mature enough, more than 10,000 crows eventually called the wetlands their winter nesting grounds. But even if Portland chose a more remote location to attract crows, the birds could still bring people together. The researchers compared UW’s viewing parties for crow arrivals to the late summer ones Portlanders throw to celebrate Vaux’s swifts’ return to Chapman Elementary’s chimney. If the swifts’ number keep dropping, as they have in recent years, crows could hold the key to Portland’s next mass birdwatching party.