On any given morning, patient bird-watchers come to Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge with tricked-out binoculars, hoping to see some of the urban wetland’s 100-plus species of migratory and resident birds, including bald eagles, peregrine falcons, and red-tailed hawks. Oaks Amusement Park’s Ferris wheel and roller coaster stand guard over the meadow. Packs of chatty moms jog by on the raised walkways, warranting glares from said bird-watchers for scaring off the wildlife with their footsteps and laughter (guilty). The 160-acre Sellwood refuge includes mammals, such as deer, raccoon, beaver, mink and otter, plus about 350 species of vascular plants.

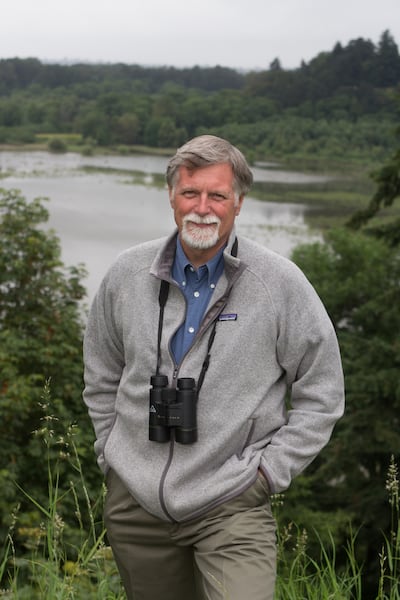

“To have that diversity of wildlife in the heart of the city is pretty damn amazing,” says Mike Houck, director of Urban Greenspaces Institute.

Now, with some upcoming changes neighboring the refuge—a sky-high drop tower at Oaks Park and a planned apartment complex—neighbors and environmental activists like Houck are organizing to make sure the wetland stays protected.

As is, the refuge is teeming with life, which is especially impressive for a former landfill.

Back in the 1950s and ‘60s, Oaks Bottom was known as the Sellwood Dump. The landfill consisted of construction and demolition debris, street sweepings and stumps, according to the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. It caught fire frequently. The fact that it became Portland’s first wildlife refuge—established in 1988—and a destination hiking trail and salmon habitat is largely thanks to neighborhood advocates who wouldn’t have it any other way.

In the late 1960s, developers started nosing around with grandiose plans to build a marina, a museum and a motocross course. Emboldened by angry neighbors who did not want to live next to an industrial park, Portland Parks & Recreation took over the property in 1969, blocking the development.

Houck has been advocating for the area since the 1970s, when he was a grad student at Portland State University. In his job at Portland Audubon, now the Bird Alliance of Oregon, in the ‘80s, he pushed for the City Council and the parks bureau to declare the area a wildlife refuge. This did not go over well.

“The first planning director I talked to told me that there’s no place for nature in the city. Boom,” Houck says. “Nobody in Portland would say that now. It would be heresy.”

To Houck, Oaks Bottom represents the change in attitude toward protecting natural areas in the city—a change also emblematized by the fact that Metro, the tri-county regional government, owns and maintains 18,000 acres of parks and natural areas in the Portland area (think Oxbow Regional Park, Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area, and Blue Lake Regional Park).

On March 25, the city approved Oaks Amusement Park CEO Brandon Roben’s permit for a new 135-foot “drop tower” ride on the park’s midway. The ride would require two zoning changes: increasing the maximum structure height from 30 to 135 feet to accommodate the ride, and allowing new exterior lighting.

When news of the ride dropped in January, organizations such as Houck’s Urban Greenspaces Institute, the Bird Alliance of Oregon, and Friends of Oaks Bottom banded together to oppose the new tower and submit public comments against the permit. They’re concerned that a structure that tall poses a threat to birds and other wildlife, and that the bright lights in particular could disorient migrating birds.

Oaks Park has since lowered the proposed ride height from 147 feet (originally proposed) down to 135 by removing a flagpole from the top, and swapped out some of the planned lights on the ride to make them more neighbor (and critter) friendly. To analyze the area, the park also hired a biologist, who concluded the lights would not be problematic for wildlife. Houck deferred expertise on the report to Mary Coolidge, campaign coordinator at Bird Alliance of Oregon. Coolidge is “baffled” that the city approved Oaks Park’s lighting plan and remains very concerned about the impacts on bird migration, especially after sunset during peak fall migration season.

The drop tower is the project on the west of the wildlife refuge. The project on the east is a proposed apartment building called Sellwood Bluff, at the corner of Southeast Milwaukie Avenue and Ellis Street. The building would be massive: nearly 200,000 square feet and seven stories with 243 units of housing and on-site parking, right on the Oaks Bottom bluff.

A March 20 meeting before the Portland Design Commission showed the developers have their work cut out for them to get Sellwood Bluff to the finish line. Neighbors complained the building would look like a cruise ship and that it’s out of scale with the rest of the neighborhood; another welcomed the addition of affordable housing to Sellwood-Moreland.

“This is probably one of the toughest sites I’ve ever worked on,” said Damin Tarlow, principal for Trammell Crow Company in Portland, the company behind Sellwood Bluff, speaking of the geographic challenges. “We’re getting squeezed on all sides.”

One more force of opposition Tarlow can ready for: the birders. Houck says the design commission ought to insist on the highest-quality anti-bird-strike windows available.

“Given that they’re sitting next to a 160-acre wildlife refuge, it’s inconceivable there wouldn’t be bird strikes,” he says. “That’s a major, major concern.”

Marianne Nelson is on the steering committee for Friends of Oaks Bottom. She lives in Sellwood to be within easy walking distance of the wildlife refuge. She attended the design meeting and is closely following the bureaucratic process of the apartment complex, which she likens to a battleship. Nelson hopes Trammell Crow listens to the neighborhood feedback and adjusts its design to be more in line with the natural beauty of the area (and more bird friendly—Nelson is in close touch with the Bird Alliance of Oregon, too).

“Anything that affects Oaks Bottom,” Nelson says, “we have our antennae up.”