I was a child in the mid- to late '90s when I first smoked pot.

It was after a messy divorce that hinged on a parent with untreated schizophrenia. And it was another family member, an adult, who introduced me to weed, among other psychedelic drugs.

Growing up, I occupied a number of households and attended a number of schools. At 32, I'm still laying the fundamental, emotional groundwork many people take for granted. By the time I left the East Coast for good in 2015—as I'd always intended, upon finishing college in 2009—I had not had health care for seven years. Instead, I relied on alternative methods, including pot.

And one day, it nearly cost my life.

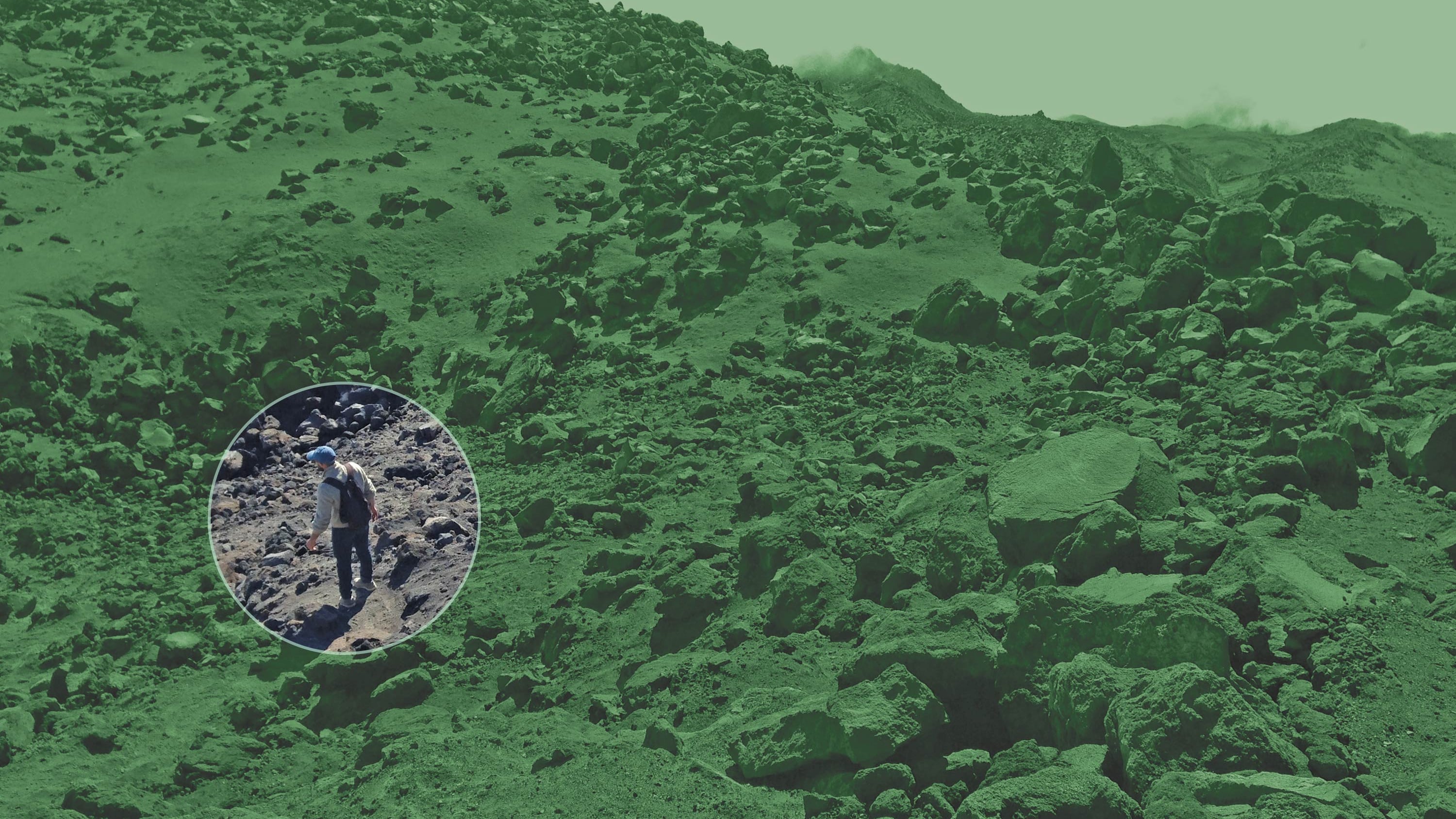

On my 29th birthday, I summited Mount St. Helens. As I labored up the final stretch—each step sinking into the ash, like a massive sand dune, that rose beneath a clear blue sky and the rim of the volcano—my heart pounded in my neck harder and faster than ever before. It was brilliant and beautiful and terrifying, all at once.

Later that night, back at home, I noticed my breathing had shortened. I felt sick. My body was tingling and my head was swirling.

I Googled "elevation sickness." I tried to sleep it off, but when I lay down, it was hard to breathe. I felt my lungs filling with fluid. I sat up straight, back against the wall, which seemed to help. If I was worse by morning, I'd go to the ER. I eventually fell asleep there, on a futon mattress on the floor of a bedroom. By morning, the wet lung had subsided.

I packed an emergency medical ration—a weed pill I had from months prior—and left for work. I was a delivery driver for a wholesale flower distributor on Swan Island, and assigned to Lincoln City that morning. I lit a cigarette, and the tingling limbs, throbbing head and nausea returned. I filled a coffee cup to go and swallowed my pill. I will get through this, I thought.

Twenty minutes outside Lincoln City, my body started tingling again, from my head to my toes, like when your leg falls asleep, except I felt it everywhere. My vision was clouding. My heart was failing.

I spotted a wide shoulder on the left and crossed over the two-way road, parking a little ways behind a Winnebago, while dialing 911. The driver of the camper watched me stumble out of the van, "white as a sheet," and communicated to dispatch where we were on the side of Highway 18.

More than an hour later, I was hooked to an IV and pumped with enough potassium to get my muscles working properly again. One of my fellow drivers picked me up, and we finished the route. I picked up the van where I'd left it on the side of the road and drove it back to Portland.

A week later, I had health insurance, having reached three months at my job—but not soon enough. The ambulance ride alone would cost $1,400. Tack on another couple of grand in debt. I made an appointment with Kaiser, and left with Prozac and Klonopin.

In his much-debated New York Times op-ed, Alex Berenson writes that the change in the public's attitude toward cannabis "has been largely driven by decadeslong lobbying by marijuana legalization advocates and for-profit cannabis companies" that "have shrewdly recast marijuana as a medicine rather than an intoxicant."

To this point, Berenson is right. Weed is not medicine—not really. But who would've known, given all the green health care crosses emblazoned outside so many dispensaries? After all, where's the profit in actually solving our national health care crisis? This is a sprawling country of exorbitant wealth and resources, where drugs of all kinds—legal and otherwise—have always been infinitely easier to obtain than actual, preventative health care.

So how could a white, male, Ivy League graduate reach the conclusion that cannabis flower is the problem, and not any of this country's monumental administrative failures that revealed themselves in the wake of the 2008 recession? It is a question he, like so many other, more fortunate Americans, are desperate to avoid. And by avoiding talking about universal health care—the need for broader reform, fewer penalties and less bureaucracy—this is how we end up employing the same, stigmatizing terminology about mental health used by eugenicists a century ago, and how a person like Donald Trump could be our guy in the White House.

To the larger point, even as more and more pot shops populate our neighborhoods, health care remains inaccessible for many Americans. Perhaps there is something wrong about that.