Every year, approximately 1.3 million people rotate through the Tillamook Cheese Factory, making the pursuit of skewering free cubes of cheddar one of the state’s top tourist interests. Similarly, the Willamette Valley’s 25,000-plus acres of vineyards have grown into a renowned wine destination, drawing vacationers from across the globe.

If all goes well this week at the inaugural Tater Tot Festival in Ontario, an Eastern Oregon city that butts up against Idaho, organizers hope to join those locations in becoming the state’s latest culinary attraction.

That may sound mighty ambitious for an agricultural community of about 11,000, situated in Malheur County, which sits at or near the top of the state’s poverty rankings based on U.S. Census data. Few people set out to vacation there and even online searches for “things to do in Ontario” primarily point you east across the border.

But the town has an exclusive claim to fame that should be just eccentric enough to entice visitors: It is the birthplace of the tater tot. That’s thanks to the resourcefulness of two local brothers who, nearly 60 years ago, found a way to transform potato scraps into the now-iconic American snack food.

Anyone just learning that the barrel-shaped potato bites have roots in Oregon certainly isn’t alone. Unlike other widely recognized grocery aisle creations, the tater tot origin story isn’t well documented, nor has it been told on a large scale.

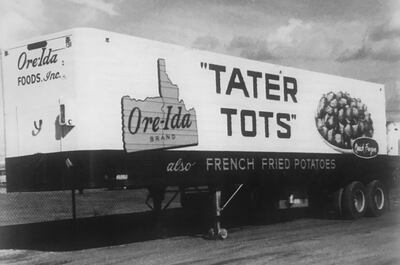

That’s likely due, in part, to the fact that Ore-Ida, the brand behind a plethora of frozen potato products, was sold to Heinz: a condiment behemoth with its own corporate lore to maintain. On top of that, most artifacts that would lure curious food tourists and hardcore tot fans—including the plywood board that led to its finger-friendly, three-quarter-inch round shape—are locked away in the original Ontario plant.

However, at least a few longtime residents of Ontario, along with surviving family members of the inventors—Nephi and Golden Grigg, two from a Mormon family of 13 children—can tell you that the tot had humble beginnings. The whole endeavor started on a 5-acre plot in nearby Vale where the brothers weren’t even growing potatoes. They were raising sweet corn and harvesting it at night to capture the kernels at peak freshness. The modest farm allowed the siblings, neither of whom had completed high school, to scrape by.

“It was pre-Depression, but they were just really, really poor. Dirt poor,” says 67-year-old Steve Grigg, Nephi’s son. “My uncle Golden is quoted as saying, ‘The Depression came and went, and we didn’t even know it.’”

The Grigg brothers may not have had much in the way of resources, but the two did possess ingenuity, which is what led to those highly unusual midnight picking missions—a first step toward keeping produce cool that later culminated in the industry-changing approach of freezing produce. The Griggs discovered that by gathering their sweet corn long after the baking Lower Treasure Valley sun had gone down, the crop would stay cool and dewy until they made their rounds the next morning, peddling ears by horse and buggy.

Sales exploded once the brothers began blanching and freezing the corn, which led to coast-to-coast shipping. They also made a foray into the potato business, to fill out the harvest calendar. Eventually, the Griggs foresaw a revolution in food preservation through the use of extreme cold, so they purchased a failed frozen food factory in Ontario even though lenders wouldn’t offer them a cent.

“It was the early ‘50s, and frozen foods were just not a thing,” Grigg says. “People wanted fresh, so [the Griggs] couldn’t get any money from the banks. It took the entire community to gather that kind of funding—a lot of farmers put up harvests of their potatoes and corn as collateral to secure these loans.”

That collective effort was enough to purchase the plant, resulting in the formation of Oregon Frozen Foods Company. Corn was still their cash cow, but there was also a steady supply of potatoes—the stockpile could get so large, they would store it in football field-length spud cellars. Once a fellow entrepreneur in Idaho discovered how to freeze potatoes without turning them black and started creating french fries, the Griggs quickly identified that as their new product and began churning out the golden splinters themselves. There was only one problem: the waste.

Machinery that cut oblong tubers into thin rods left behind an excess of shavings they had no use for. Never ones to needlessly discard, the brothers initially sold the byproduct to farmers as cattle feed. But frustrated that so much premium potato simply ended up as cow cud, the Griggs went to work finding a way to turn the scraps into something appealing for humans.

They diced the shavings, tossed them with flour and seasonings and then—to achieve the perfect miniature log shape—drilled different-sized holes in a piece of plywood. Later dubbed “the holey board,” there are accounts of Nephi shoving the mixture through the openings on one side as Golden sliced on the other. After a quick bath in the fryer, the product that would come to define their company was created.

Multiple narratives tell how the name “tater tot” came to be, but Nephi’s son prefers the version in which a factorywide contest led to a snappy trademark.

“One of the employees there—Clora Lay Orton—she won,” Grigg says. “‘Tater’ for potato and, of course, ‘tots’ for small. Makes perfect sense to me.”

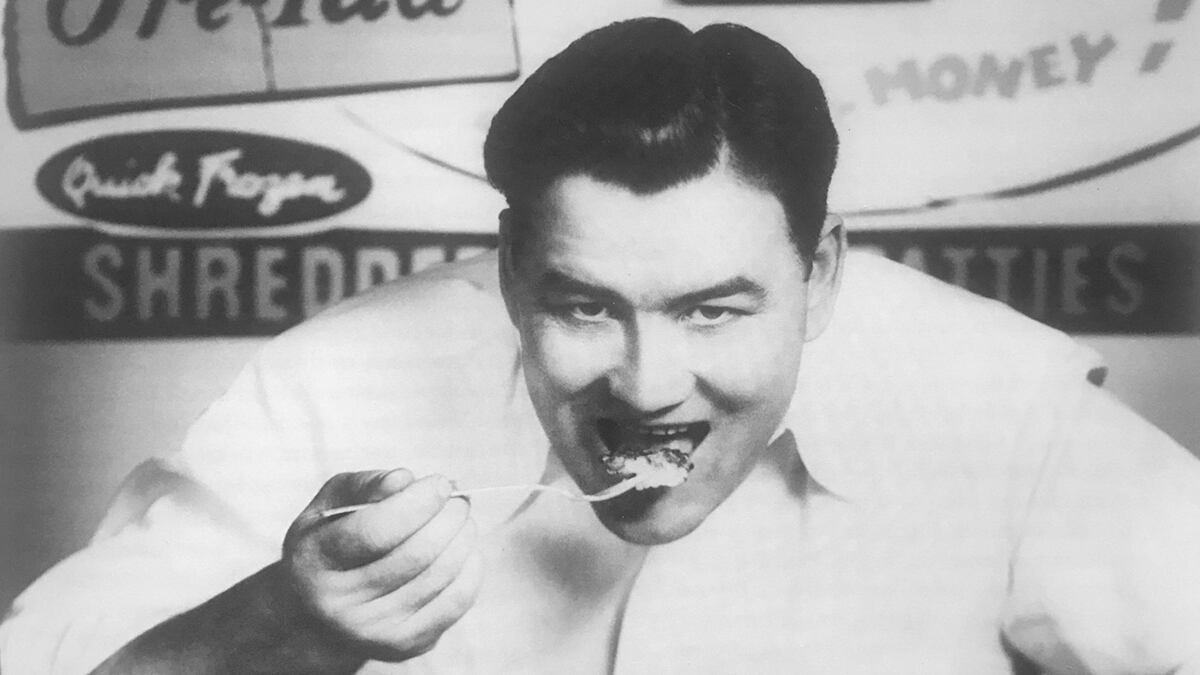

Everyone agrees, however, that the tot truly arrived in 1954. That was the year Nephi packed his bags—including a suitcase filled with tater tots on dry ice—and headed to the National Potato Convention in Miami. The extravagant Fontainebleau played host, a brand-new hotel on a long strip of palm-lined land overlooking the ocean, but a rural Oregonian who grew up in poverty was about to knock the gilt off of that venue with his invention.

Nephi had his biggest audience yet—a focus group of hundreds of men who traded in potatoes. Grigg, who describes his father as “a little more gregarious and humorous” than most, sweet talked his way down into the kitchen, tater luggage in tow, then convinced the chef to serve his tots to the attendees.

“They fried them up and he put them on little saucers on the breakfast tables as kind of a treat,” he says. “And they just disappeared. My dad said they were ‘gobbled up quicker than a dead cat can wag its tail.’ That’s really the launching of the tater tot into the world.”

Despite the enthusiastic reaction at the convention, Ore-Ida’s new potato knobs didn’t immediately take off in the marketplace.

“When they first launched it, the cost was so low that nobody thought it was worth anything,” Grigg explains. “It wasn’t until they increased the price and made it a premium product that people realized it was something. Their honest, small-town upbringing came through in that regard. They didn’t know how to price and move it.”

Once they caught on, though, tater tots catapulted the company to a new level: The Griggs opened a second factory in Burley, Idaho, began planting thousands of acres of land with potatoes just for tot production—scraps no longer sufficed as the supply. The brothers sold the company to H. J. Heinz in 1965 for nearly $30 million, with Nephi making the trip to Pittsburgh to finalize the deal.

“[My dad] walked into the boardroom, and he said, ‘You could just smell the money,’” Grigg recounts. “They cut that check and handed it to him, and he folded it in half, stuck it in his pocket and said, ‘Thanks, boys!’ They were all just shocked. He was doing that to pretend like it was no big deal, but it was a huge, huge deal.”

Given the versatility of the potato—it’s a food that can be prepared in dozens of different ways—the tater tot’s ability to stand out speaks to its originality. It’s been venerated in both culinary and pop culture as the after-school freezer snack savior, the perfect late-night bar companion, and a cafeteria staple.

“I think it was just so unique,” says Grigg about its enduring status. “It was convenient. It was funky—it had a funky name. Of course, the movie Napoleon Dynamite didn’t hurt.”

It’s no wonder, then, that Ontario has decided to seize its legacy and promote it with glee.

“When you start talking to locals, a lot of them have worked at the [Ore-Ida] campus,” says Charlotte Fugate, a Tater Tot Festival organizer and president of Revitalize Ontario, the nonprofit behind the gathering. “They’re proud of the fact they worked there, and they’ve got kids now working there.”

At the event Sept. 17-18, which the Kraft Heinz Company helped fund with a $50,000 contribution, you’ll find what should be the largest concentration of fried potato nuggets ever assembled, including multiple presentations by the preliminary winners of a cooking contest—attendees get to anoint the grand prize winner, who will receive an oversized silver bowl to display as proof of their tater mastery. Feats of stomach-expanding bravery will also be on display in the form of a tater tot eating contest—participants have two minutes to pop as many tots as they can.

Beyond celebrating the tot, however, is a larger goal for Ontario—to boost its reputation and become an Eastern Oregon destination that attracts travelers year-round, whether they’re seeking out the factory where the tater tot originated, or simply stopping to admire the recently refurbished historic downtown.

“We had a lot of people come through before, and they said, ‘Well, your town is dirty and you’ve got farm equipment sitting around, and it’s not very practical for attracting businesses,’” Fugate said. “So our goal was to clean up the town, get it sparkling and make things happen.”

Steve Grigg will attend to welcome the crowd this week, but even after the festival has wrapped, he plans to continue to try to amplify his family’s story and the history of the tater tot so that both receive the recognition they deserve.

“I’m going to revisit my efforts to get a display in the National Museum of American History,” he explains. “I thought, wouldn’t it be great to get that holey board in there? You know, [patrons] walk over here and they see Dorothy’s ruby slippers and they see a Philo T. Farnsworth television set. I think they should walk by and see the Ore-Ida holey board and a story about the tater tot. So that’s my next endeavor, to see if I can make that happen.”

GO: Tater Tot Festival, South Oregon Street and Southwest 2nd Avenue, Ontario, Ore., tatertotfestivaloregon.com. 4-9 pm Friday, 11 am-9 pm Saturday, Sept. 17-18. Free.